Executive Summary and Key Recommendations

Southwest Virginia’s coal mining legacy has created a range of environmental issues that persist to this day. One manifestation of this legacy is Garbage of Bituminous (GOB) piles containing mining waste and coal discarded by mining companies over decades. Virginia Energy (formerly the Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy) has identified 245 legacy GOB piles in Virginia concentrated in the southwest region.

These legacy piles create a range of environmental and safety hazards and discourage economic activity in the southwest region. GOB piles degrade Virginia’s waterways through Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) and the leaching of other pollutants. The piles are also often unstable, creating a public safety hazard, and are at risk of catching fire, leading to dangerous and uncontrolled burning. These challenges complicate economic revitalization efforts in an area that trails the state’s economic and demographic trends.

Assuming remediation occurs at the current rate of about 400,000 tons of GOB per year, ESI quantifies the benefits from rectifying GOB piles at nearly $1.6 million in year one, accelerating to $5.64 million in year 20. Over 20 years, benefits total more than $72 million in nominal terms, averaging $3.61 million per year.

Whether considered from an environmental, public health, or economic development perspective, all efforts should be made to remediate legacy GOB piles in southwest Virginia.

Recommendation 1 >> A programmatic effort should be undertaken to remediate the GOB piles in southwest Virginia.

Remediation can take different forms. The most appropriate form of remediation for one GOB pile may not be suitable for another; some GOB piles could be remediated “in place.” Water treatments, stabilization, and revegetation are all processes that can be used to limit the impacts of GOB piles.

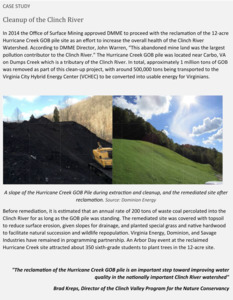

GOB piles can also be removed. The piles can be disposed of in lined landfills or at active mine sites. Some piles could also be re-mined, separating the waste coal and putting it to some beneficial use, such as combustion for electricity generation. Dominion’s Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center (VCHEC) in Wise County, located near many of the legacy GOB piles, has the capability to burn waste coal. This approach has been the predominant way that GOB piles have been removed in Virginia in recent years. Choosing to combust GOB for electricity creates market incentives for remediation, but also runs counter to Virginia’s commitment to transition to clean energy.

Choosing the best method for remediation depends on the characteristics of a particular site. The location of the site in relation to waterways and underground drinking water is a crucial consideration. When determining whether a site is optimal for remediation, the site should prioritize the harm caused by a particular pile. A pile’s proximity to transportation channels, local communities, and existing or soon-constructed landfills could significantly impact the most suitable method of remediation. The particular characteristics of a pile, its composition, percentage of waste coal likely to be reclaimed, stability of the pile, and extent of pollutants present, affect prioritization and remediation choices. Property ownership and potential liability issues can also differ among the various piles, as well as permits required to engage in remediation activity.

Recommendation 2 >> Virginia should conduct a site-by-site analysis of the state’s inventory of GOB piles to include information that will allow the state to prioritize remediation efforts and determine the most appropriate method of remediation for each site.

A site-by-site analysis of the GOB piles should be undertaken to prioritize the most in need of remediation and inform the most appropriate method of remediation. This should include groundwater testing and possible monitoring at each site. Such an undertaking calls for the State’s involvement.

As this report explains, there is a significant market available for GOB pile remediation through various sources. The most applicable source is the federal Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Fund under Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA). The AML Fund is particularly appropriate because it recently received 11.3 billion dollars over 15 years with the recently enacted Infrastructure Bill.

Virginia Energy should apply for AML funding to support the inventory efforts and site-by-site analyses. Virginia Energy should also develop standards for prioritizing which GOB piles should be remediated first; then, remediation efforts can begin as soon as individual analyses are completed.

Recommendation 3 >> Virginia should launch a GOB pile remediation initiative that employs coal industry workers and reclassifies GOB pile remediation as a top priority for its AML funds.

GOB piles have long been relegated to Priority 3 status under SMCRA, which has limited Virginia’s ability to target GOB remediation directly. However, the 2021 Infrastructure Bill affords Virginia new authority when expending AML funds appropriated under the Bill. It assigns any level of priority to AML reclamation projects so long as they provide employment for current and former coal industry employees. This authority to determine project priority is additional to the traditional three priority levels prescribed by SMCRA. Virginia should launch an aggressive GOB remediation initiative that employs coal industry workers and explicitly reclassifies GOB piles as a higher priority.

The high prioritization of remediating southwest Virginia GOB piles would be consistent with Virginia’s recent laws, and policies in support of environmental justice communities. The economics and demographics of southwest Virginia, combined with the disparate public health impact the region has felt from extensive coal mining activity, assure that many localities qualify as environmental justice communities. By law, Virginia must consider the impacts to those communities in making decisions on energy policy.

Recommendation 4 >> In its 2022 AML grant application (and in future years), Virginia Energy should request sufficient funds to cover GOB pile remediation efforts.

Under the 2021 Infrastructure Bill, state applications for AML grants may aggregate bids into larger statewide or regional contracts. Virginia should solicit bids for a large-scale effort to remediate GOB in southwest Virginia and aggregate those bids in the 2022 AML grant application.

Recommendation 5 >> Virginia should create an atmosphere conducive to the remediation of GOB piles, funding for such remediation efforts, and providing necessary tools that are accessible to private entities, localities, and non-profits.

Whether pursued through the General Assembly, the Governor’s Office, or various state agencies, there are several non-mutually exclusive options Virginia could pursue to maximize the opportunities for funding to remediate southwest Virginia GOB piles:

-

Many of the funding opportunities discussed in this report can only be pursued by the State or with the State as a partner; the State should commit to pursuing such opportunities and partnerships.

-

Investor-owned public electric utilities could be encouraged or required to pursue remediation funding, to partner with localities and academic institutions as required for funding, and support remediation efforts.

-

Many funding opportunities are only available to nonprofits, private entities, localities, and academic institutions, or collaborations among such entities. Virginia Energy should establish a database of funding opportunities so these entities can coordinate and initiate efforts to seek remediation funding.

-

Virginia should commit to increasing the State’s capacity (personnel, equipment, expertise, etc.) to permit remediation activities, assist with GOB pile assessments and groundwater monitoring, and undertake mass remediation projects.

-

Virginia should create a program or provide incentives for the creation of such a program, to employ and/or retrain displaced miners to work on remediation projects. In addition to such programs, other funding opportunities are available involving the employment and/or retraining of current and displaced coal miners if the State prioritizes AML funds.

-

In seeking federal and other funding, Virginia should emphasize that southwest Virginia is home to many environmental justice communities; Virginia should prioritize environmental justice communities in determining how to utilize limited infrastructure resources.

-

In the event site assessments support coal re-mining from GOB piles for power generation, Virginia could create a tax credit or other incentives for burning waste coal or making other productive use of it.

1. Report Overview

This study aims to identify options, obstacles, and opportunities for the potential remediation of legacy waste coal piles, known as “GOB piles” or “coal refuse piles,” in southwest Virginia. The Appalachian School of Law (ASL) has collaborated with Econsult Solutions, Inc. (ESI), a consultancy specializing in economic and public policy issues, to undertake this analysis. This work is funded in part by a grant from Dominion Energy.

This study is not intended to endorse a particular policy approach to this complex challenge. Instead, this study intends to identify relevant economic, legal, and environmental considerations for state and local policymakers who wish to address the ongoing challenges presented by legacy GOB piles.

After this Overview, section 2 of the report begins by explaining southwest Virginia’s coal mining history and the legacy Garbage of Bituminous (GOB) piles it left behind. Various environmental and public health impacts of these GOB piles and attempts to quantify the economic benefits of remediating them will be discussed in section 3.

Section 4 explores the remediation of the GOB piles in more detail. First, it examines potential remediation approaches. These include approaches that lessen GOB piles’ adverse impacts; removal and safe storage of the GOB; and re-mining the piles for waste coal that could be used for electricity generation. Section 4 also considers the legal and regulatory framework pursuant to which remediation would take place. Relevant federal laws include the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA), the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Clean Water Act, and other regulations designed to address the handling of coal ash and the combustion of waste coal. Finally, section 4 examines Virginia’s transition to a clean energy economy, and how it may impact the preferred remediation approach.

The operating trends and regional economic impact of Dominion’s Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center (VCHEC) will be discussed in section 5. As the VCHEC is the only facility in Virginia where combustion currently occurs, the re-using the GOB as a fuel source should be examined.

Section 6 discusses potential funding sources for remediation projects. Many communities in southwest Virginia may qualify as “environmental justice” communities due to their relative poverty and the disparate public health impacts attendant to the region’s coal mining history. Qualifying as an environmental justice community opens up additional funding sources. The most clearly applicable funding source is the Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Reclamation Fund; the recently enacted Infrastructure Bill appropriated $11.3 billion over 15 years for the AML Fund. Other funding sources are also explored, including EPA environmental justice programs, Brownfields programs, and American Rescue Plan programs.

Finally, the Conclusion in section 7 extracts key recommendations from our analysis for policymakers to consider.

2. Virginia’s Coal Mining History and Legacy GOB Piles

The rise and decline of southwest Virginia’s coal industry, and the origins and status of the legacy GOB piles in the region are extremely apparent.

Virginia’s coal mining history is long and has significantly shaped the state’s southwest area. Coal was discovered in southwest Virginia in 1701 and first produced in 1748. The southwest area of Virginia is part of the Appalachian Plateau, and is a predominantly bituminous region (see Figure 2.1).

Originally, iron was the most valuable natural resource in Virginia. However, more efficient iron furnaces in Pennsylvania overtook the Virginia furnaces. After the Civil War, a heavy investment in railroad expansion occurred in the Virginia coalfields, especially in Buchanan, Dickenson, and Wise counties.

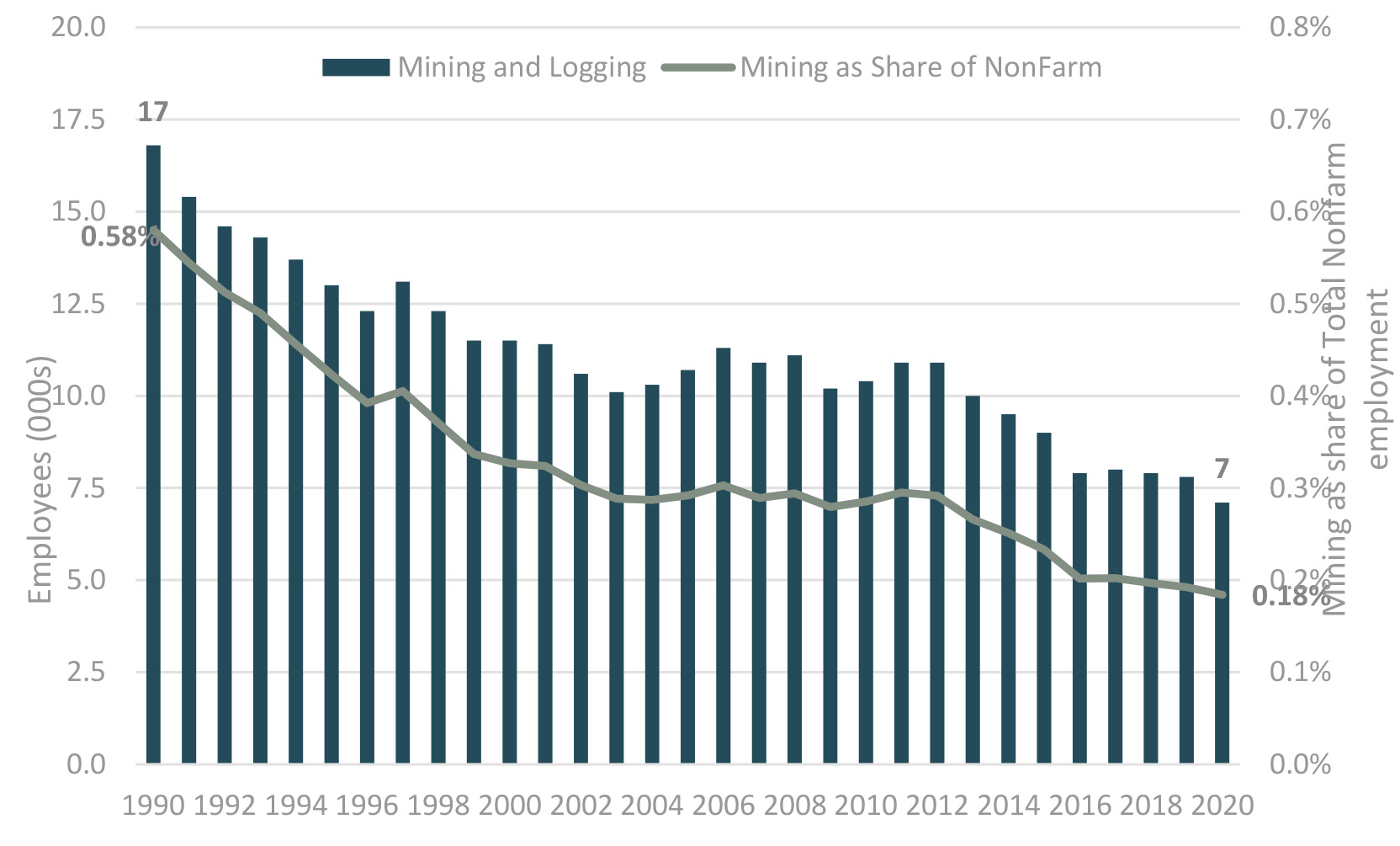

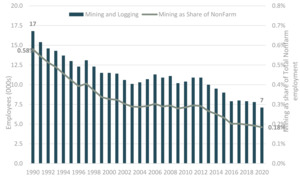

As deep mining was replaced with surface mines, and automation dramatically reduced the number of miners needed for every ton of coal produced, the number of miners in southwest Virginia dropped.[1]

Since the peak in 1990, coal production in Virginia has continuously declined. In 2020, Virginia produced 9.7 million short tons of coal; only 20% of the 1990 annual production level.[2] While production levels have declined steadily, the value of coal as a Virginia export has only, recently, declined. Global demand bolstered the value of Virginia’s coal through the 2000s. However, following the “Great Recession,” and the subsequent spike in coal value, the value has fallen sharply. Similarly, many mines have closed throughout Virginia: in 2001, there were 190 actively operating mines in Virginia, and by 2020 the number was down to 62.[3] The negative shift in the industry, both recent and historic, has created a myriad of issues with which Virginia – and particularly southwest Virginia – must now contend. Recent declines in the mining industry have created a need for economic development to revitalize and strengthen the area.

As mining activity curtailed and eventually, left Virginia, a significant number of abandoned mines and piles of coal were left behind. Virginia was host to over two centuries of coal production before significant legislation was introduced to mitigate and control the impact of mining activity. Coal mining operations left behind extensive waste and remains for the extensive period of early coal production in Virginia. These remnants pose a serious, continuing problem to the people of Virginia.

Coal refuse piles are mounds of “waste coal,” and other mining refuse that were discarded during the mining and coal cleaning processes. These piles in southwest Virginia are commonly referred to as “GOB” piles, and can often weigh tens of thousands of tons. With limited environmental regulations in place, pollutants leach from the coal refuse and erode local streams and soil. These GOB piles pose serious threats to health and safety, and actively damage environmental conditions as well as economic conditions.

It was not until 1977 that the federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) was enacted, which triggered the Virginia Coal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1979 (Va. SMCRA). The state regulation of mining activity was strengthened through the establishment of the Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy (DMME) in 1985.

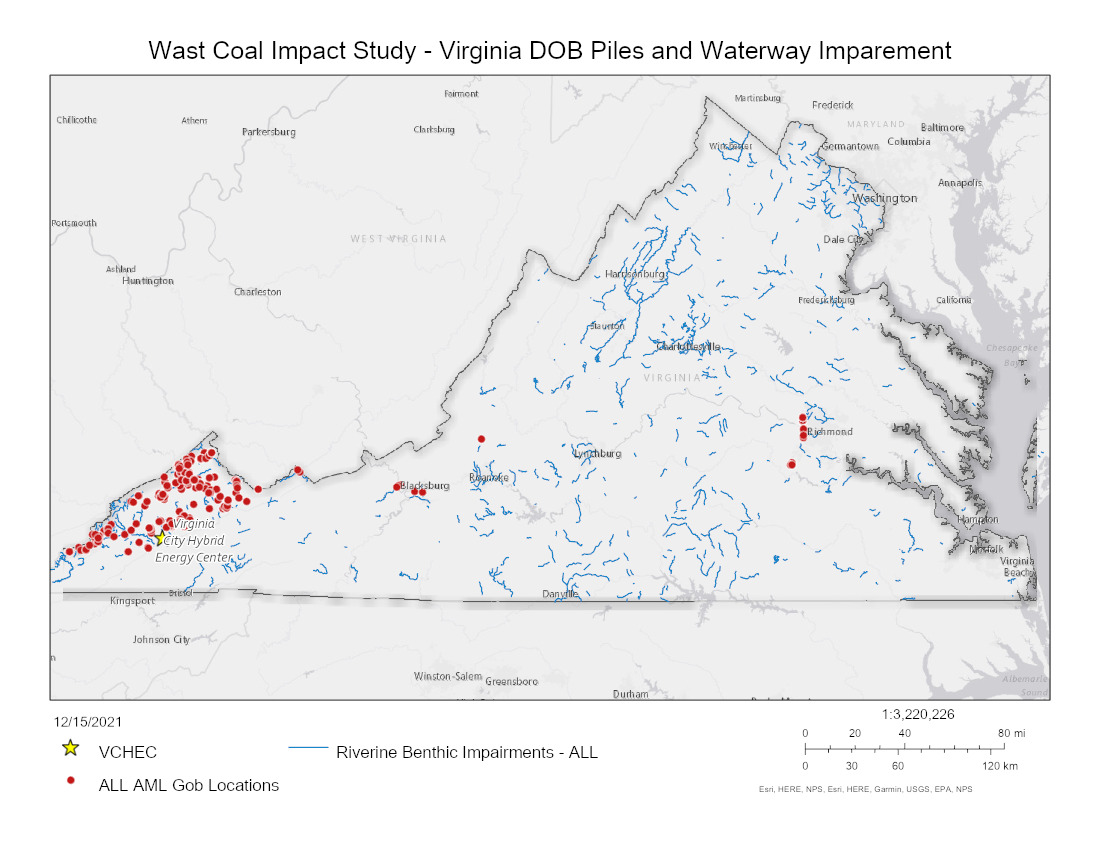

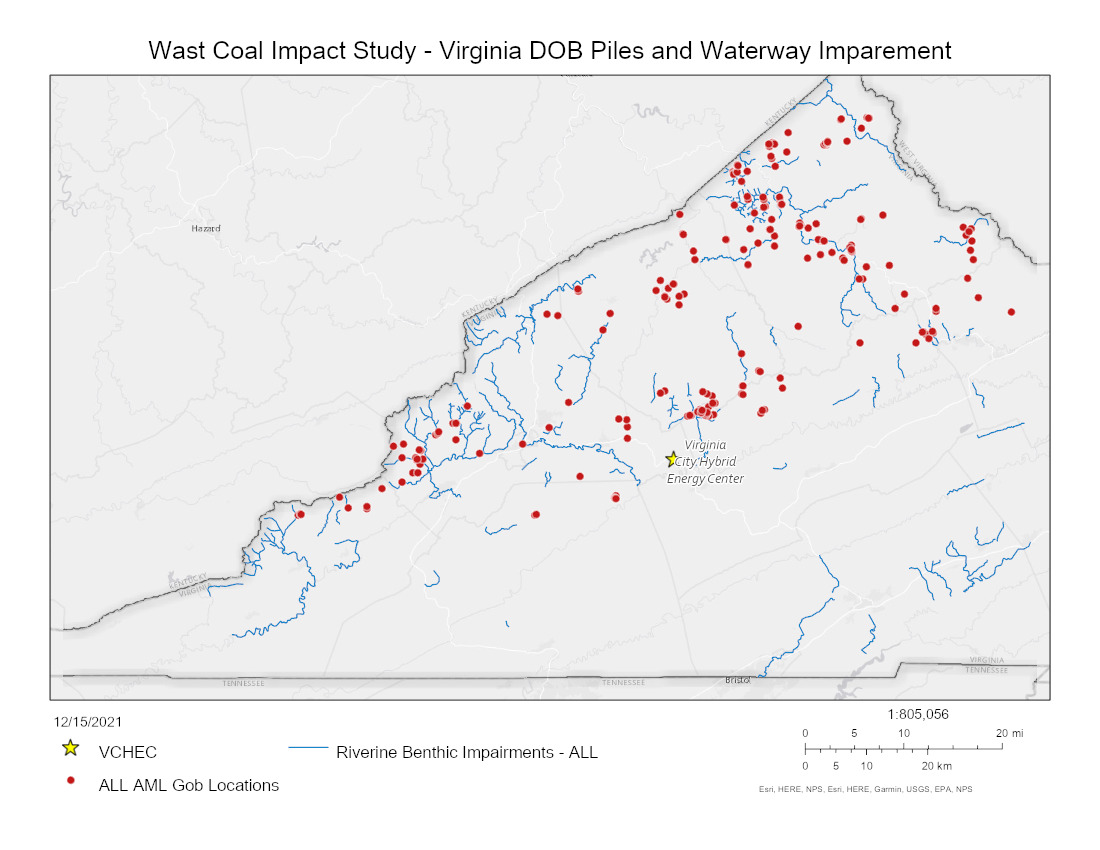

Virginia Energy (formerly DMME) has done significant work to assemble an inventory of GOB piles and their locations. While the inventory is acknowledged to be incomplete, Virginia Energy documents at least 245 GOB piles in the Commonwealth.[4] These piles’ size, weight, and composition have not been fully surveyed (see Figure 2.2).

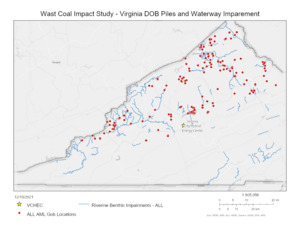

The landscape of GOB piles and mining remnants follow the geography of coal deposits in the Commonwealth. As a result, these piles – and the accompanying hazards and environmental damages – are heavily clustered in southwest Virginia.

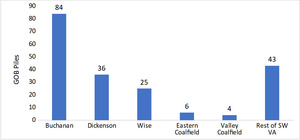

A Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis was taken by ESI of nearly 200 identified GOB piles classified as “unremediated” in the Virginia Energy dataset. More than 80 of such piles are located in Buchanan County alone, and the other 114 piles are located in Dickenson, Wise, Russell, Tazewell, and Lee Counties. The remainder of the piles are gathered around the Valley and Eastern coalfields in the middle and the east of the Commonwealth, respectively (see Figure 2.3).

Many of these piles are located near populated areas, posing not only a health hazard but also a blight too, both, quality of life and real estate values. One-hundred-fifteen GOB piles are located within 10 miles of some of the densest population centers in affected counties (see Figure 2.4).

3. Environmental Impacts/Liabilities of the GOB Piles and Efforts to Remediate Them

This section reviews research and develops an economic framework to monetize the costs of environmental degradation from legacy GOB piles and the potential benefits of remediation.

-

Section 3.1 reviews impacts on water quality and defines avoided costs for water treatment achievable through the remediation of GOB piles.

-

Section 3.2 reviews impacts on public health and safety, and defines avoided costs and social value generated by avoided injuries from the remediation of GOB piles.

-

Section 3.3 discusses the reclamation of land enabled by the remediation of GOB piles, and the potential economic value generated through direct reclamation and impact on adjacent properties.

-

Section 3.4 aggregates each category’s benefits into a valuation framework for GOB pile remediation.

The environmental and public health benefits of remediation result in different forms to different beneficiaries, including the public at large, private landholders, and state and local government entities. ESI employs a mix of analytical methods to quantify these benefits in economic terms.

In addition, some of the benefits from the remediation of environmental hazards are cumulative over an extended period because the benefits continue for several subsequent years. Total benefits are expressed in this analysis as the net difference between societal benefits accumulated (a positive number) and costs avoided (a negative number) and are modeled over a 20-year timeframe to account for the cumulative effects.

As discussed in Section 2, no comprehensive inventory exists that indicates the number of tons of coal refuse represented by Virginia’s legacy GOB piles. Absent this benchmark; it is not possible to define the economic benefits of remediating all GOB piles across Virginia. Remediation of all piles is also not likely to be achievable within a realistic window for analysis.

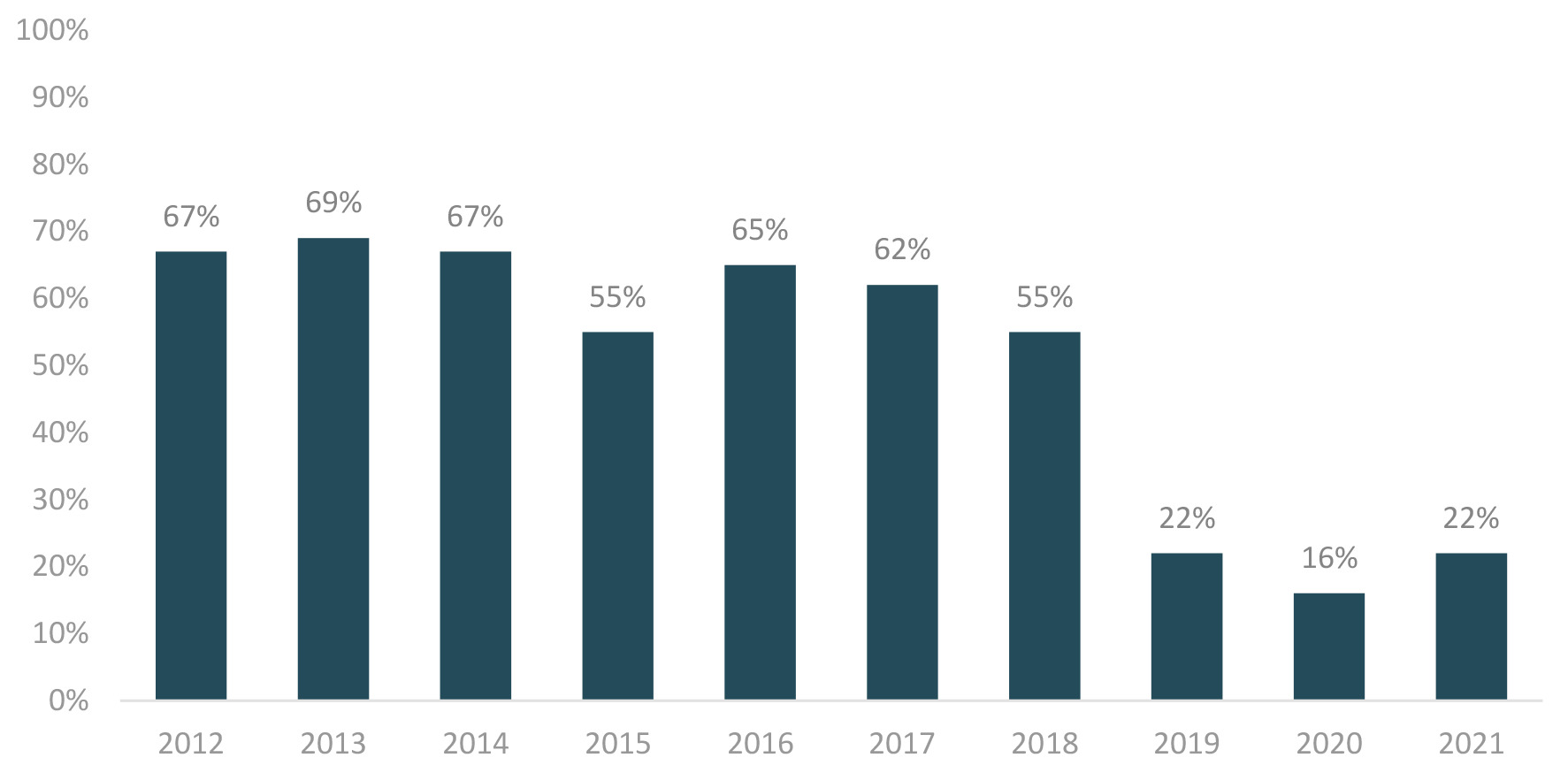

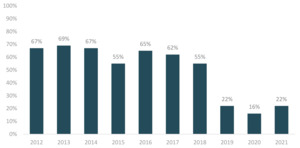

In order to provide a relevant benchmark for analysis, revenue generated from remediation is based on the annual level of coal refuse removed for energy generation at the VCHEC. Based on operational data from the VCHEC from 2012 to August 2021, the annual remediation level is estimated at 400,000 tons per year.[5]

The use of this benchmark does not indicate that these benefits are unique to activity undertaken by the VCHEC since these benefits could be achieved through other approaches that remove coal refuse and remediate the sites. The framework does seek to compare the benefits of this annual activity level to the costs the state and private actors ultimately accrue if the state’s legacy coal refuse piles remain unaddressed.

3.1. Water Quality Impacts

Acid Mine Drainage (AMD)

Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) is a phenomenon exclusive to the mining industry that generates billions of dollars worth of negative externalities. AMD occurs when surface and groundwater percolate through refuse coal piles leading to a reaction between pyrite, oxygen, and water (surface or ground). The reaction creates acidic runoff containing sulfuric acid and dissolved iron compounds, which have their own unique effects on the environment. The former gives the water an acidic property serving as a catalyst for further corrosion of minerals, which adds to the pollution of soil and waterways over time, dissolving other metals such as copper, lead, and mercury.[6] The latter is responsible for the accumulation of silt content, causing a rustic tint in affected waterways. However, both serve to devalue, disrupt, and deteriorate ecosystems and inhibit their ability to sustain marine and plant life.

Virginia’s Stone Creek is an example of the negative effects that AMD can impose on waterways and their habitability. A buildup of sedimentation and the continuation of dissolved solids from abandoned mine lands resulted in the degradation of the 5,251-acre watershed. The analysis of the affected waterway by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) found it to be lacking the ability to sustain aquatic life and categorized it as a “severely impaired” to a “moderately impaired” body of water.[7]

To remediate the impaired watershed, the DEQ and Virginia Energy developed a benthic total maximum daily load (TMDL) and implementation plan. The plan assesses the maximum daily load of pollutants a body of water can sustain and still meet water quality standards. To meet the TMDL and initiate the reclamation of Stone Creek, the DEQ reclaimed the disturbed mine lands and those adjacent to it, and imposed sedimentation control practices for the watershed. As a result, the water quality of Stone Creek has improved tremendously, resulting in readings above the minimum required threshold in the fall of 2009 and 2010.[8]

Impacted Waterways

Virginia has more than 100,000 miles of rivers and streams, 248 publicly owned lakes, more than one million acres of coastal and freshwater wetlands, and over 120 miles of Atlantic Ocean coastline.[9] Statistical data provided by the EPA shows that, as of 2018, 47.2% (19,588 miles) of the rivers and streams being monitored in Virginia were in suboptimal conditions to support aquatic life. Further, the primary sources causing strain on the habitability of those waterways were due to the presence of sedimentation/siltation and high levels of phosphorus.[10] Of the 47.2% of impaired rivers and streams, 38.1% experience high levels of sedimentation/siltation, while 24.1% display high levels of phosphorus.

A key indicator used to determine the habitability of waterways is the abundance of benthic organisms present. Benthic organisms are aquatic species that live in or on the bottom of a body of water. According to Virginia’s water quality standards, waters that display a degraded benthic community are considered impaired. GOB piles directly affect Virginia’s streams and waterways by producing acidic runoff containing sulfuric acid and dissolved iron compounds that leak into waterways and inhibit habitability. One of the most detrimental pollutants to benthic life is the accumulation of dissolved iron compounds that increase levels of siltation and sedimentation in impacted waterways.

Figure 3.1 shows the clustering of GOB around southwest Virginia’s waterways, increasing the likelihood of impairment and loss of aquatic life. It is also important to note that 27 piles are within a 10-mile radius of the Powell River, and four piles are within a 10-mile radius of Virginia’s Clinch River watershed. These represent two of Virginia’s most prominent watersheds, connecting to hundreds of other waterways and tributaries. The negative and pollutant effect of each GOB pile compounds as affected waters flow through the watersheds.

Implications for Revegetation

Revegetation is a common, yet difficult process for waste coal remediation and reclamation. Under SMCRA and state regulations, refuse piles must be able to sustain vegetation for a period of five years before the reclamation is considered successful.[11] Additionally, water, leachate, and runoff must meet water quality standards and show no signs of relapse in the future. Another new feature is the storage and structure of modern refuse piles. The regulations require piles to be placed on an incline to reduce the overall acreage of piles and minimize the amount of disturbed land.[12]

Sloped surface piles present several impediments to revegetation: (1) difficulties in placing soil amendments atop a sloped surface; (2) difficulties for soil to absorb and retain water due to increased runoff – further exacerbated by the compaction of refuse piles; (3) and the climate of sloped surfaces being subject to the direction in which they face.[13] Another problematic aspect of the revegetation process is the unpredictability of the geological components of each pile. Southwest Virginia coal seams tend to be lower in sulfur than other coal seams found along the Appalachian Mountains, indicating a higher level of acidity.[14] In fact, “the average fresh refuse material in Virginia requires 10 tons of calcium carbonate per 1,000 tons of raw refuse to neutralize the acidity.”[15] Moreover, the fertility of soil tends to be lacking in terms of nitrogen and phosphorus for plants.

Economic Value of Improved Water Quality

An analysis by Dr. Paul Ziemkiewicz, Director of the West Virginia Water Research Institute, established the potential acidity reduction from removing coal refuse for use at the coal refuse plant in Grant Town, West Virginia, and replacing it with coal ash. Scaling these benefit levels to the activity of Dominion Energy’s VCHEC indicates that the annual removal of 400,000 tons of coal refuse produces a reduction of more than 150 metric tons of acid loadings annually.[16] Further, the deployment of 978,000 tons of coal ash annually produces a reduction of nearly 403 metric tons of acid loadings each year.

To combine these values, an “overlap adjustment” of 50% is conservatively applied to account for situations where coal ash is returned to the original site where coal refuse was re-mined; thus, combining to lessen the impacts on the same waterway. The unique annualized savings in acid loadings from coal refuse removal and coal ash total approximately 360 metric tons in year one. Importantly, this amount accumulates in future years, because remediation that takes place in year one continuously delivers benefits in subsequent years.

Earlier work by Ziemkiewicz, Skousen, and Simmons found that the industry standard treatment cost for a metric ton of acid loadings with caustic soda (NaOH) was $500/ton/year. Applying this figure to the annualized volume of acid loading reduction from industry activity yields an avoided cost of about $180,000 in year one. This figure accelerates over time, since avoided cost benefits from prior years remain in place.

Notably, this figure monetizes only the benefits from a reduction in acid loadings and the associated treatment savings. The removal of coal refuse also reduces loadings of iron, aluminum, manganese, and sulfate. Conversely, this figure does not attempt to monetize any costs associated with using coal ash in this manner.

3.2. Public Health and Safety

In addition to water quality impacts discussed above, GOB piles pose several threats to public health and safety, including air quality impacts, the potential for destructive collapses, and injuries from unsafe recreational use. Coal dust from piles is emersed in the wind and spread in nearby communities, creating adverse effects.[17] Coal refuse piles can also ignite spontaneously or through human intervention, such as garbage burning.[18] Once ignited, fires may continue to burn for decades due to the coal refuse’s continuous fuel source. Further, “methods to extinguish or control AML fires . . . are generally expensive and have a low probability of success,” according to a report from the U.S. Bureau of Mines, which describes the fires as “a serious health, safety[,] and environmental hazard.”[19] As a result, piles that have caught fire typically are upgraded to “Priority 1” AML features due to the extreme danger associated with public health, property, and safety.

While there is a significant amount of research studying the impacts of GOB piles, there have not been very many legal cases recently brought before the United States government. Below, we consider the impacts on air quality resulting from adverse impacts of GOB piles, such as spontaneous combustion, and incidents from the instability of GOB piles in other countries. Unsurprisingly, the few cases addressing the liability associated with the health and safety impacts of GOB piles within the United States have come from the Appalachian coal states of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, and, recently, the Illinois Coal Basin.

Impacts for Air Pollution (U.S. litigation)

Legal claims stemming from the impact of GOB piles on public health can be traced back to the mid-1930s in Versailles Borough v. McKeesport Coal & Coke Company.[20] The Pennsylvania private nuisance case was brought by the city and borough against a coal company for health impacts residents suffered due to nearby burning of GOB piles.[21] The city and borough introduced 51 witnesses who spoke of conditions such as hay fever, asthma, irritated throats, coughs, and other similar symptoms resulting from exposure to the fumes.[22] Later, the defense produced 71 witnesses who claimed they suffered no ill effects from the nearby GOB piles.[23] The court ultimately found there was no evidence provided that “warrant[ed] the assumption that the health of anyone [was] being imperiled” by the fumes from the GOB piles.[24] Instead, the court indicated the injuries resulted from annoyances posed by dust, smoke, and the odor.[25] While the court did not hold the burning GOB piles posed a significant risk, by July 1964, the Pennsylvania Department of Health had determined that burning GOB piles constitutes a serious air pollution risk.[26] Studies conducted in Pennsylvania found that burning GOB piles emit oxides of sulfur, which can interfere with visibility throughout the area. The study shows that the emitted oxides of sulfur adversely affect the health of residents and impact the property of nearby communities.[27]

In 1940, the West Virginia Supreme Court concluded that the fumes from a burning GOB pile could constitute a public nuisance resulting in civil liability.[28] In this case, residents alleged that the fumes adversely impacted the health of the community and amounted to a public nuisance.[29] There was testimony at trial that the atmosphere was “pungent with the odor of burning sulphur,” impacting both the residents’ health and their ability to enjoy their own property and land.[30] More specifically, residents claimed that the gases resulted in burning sensations in the nose, throat, eyes, and respiratory tract, causing headaches, coughing, loss of appetite, and sleeplessness.[31] As for their ability to enjoy their land, many residents stated that they had to keep their homes sealed to prevent the fumes from entering the house.[32] After air tests were presented to the court and testimony given from several doctors and current and previous residents, the court held that the fumes from this particular burning GOB piles constituted a nuisance.[33] While the Supreme Court upheld the ruling, it explicitly stated that the decision does not mean every burning GOB pile constitutes a nuisance.[34]

Over a decade later, in 1956, the Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia heard another case, Koch v. E. Gas & Fuel Assocs. Here, the court held that owners of parcels containing GOB piles cannot utilize their land and allow GOB piles to burn if the fumes are injurious to neighbors.[35] This case centered on the negligent use and operation of the GOB pile by failing to prevent and subsequently maintain burning fires, resulting in the release of poisonous gases, such as sulphur dioxide.[36] The decision relies on Rinehart v. Stanley Coal Co. as precedent in making its determination.[37] In Rinehart, the coal company noticed the spontaneous combustion, and unsuccessfully attempted to extinguish the fire with water and ‘bug dust.’[38] The Court held that the company, “knowing the highly inflammable and combustible quality of the `bug dust,’ was clearly negligent in depositing it with the other mining refuse in a huge dump covering several acres, as the machine cuttings, not sold as coal, could have been, and part of it was, deposited elsewhere.”[39] Similarly, the Koch court held that a plea of assumption of risk cannot be used to “bar damages to the plaintiffs which have accrued since the plaintiffs moved into and on their property, and after the trust association had been notified or by the exercise of reasonable care should have known, of the injurious effects of its gob pile or gob piles.”[40] Ultimately, the Court reiterated that “[a] person in possession of land is required [ ] to use it as not to injure the property of another person.”[41]

Another Pennsylvania case involving the violation of a municipal ordinance shows that liability may be found against a possessor of property where a burning GOB pile is located, even if the possessor did not create the GOB pile or cause the resulting fire.[42] In 1959, the Superior Court of Pennsylvania decided a case where a gentleman was fined $100 for violating the Smoke Control Ordinance of Allegheny County for a fire burning from a GOB pile emanating smoke and obnoxious fumes.[43] The smoke and fumes resulted in health issues of, both, people and animals, as well as property damage.[44] The ordinance stated that any open fires resulting from coal refuse had to be extinguished by January 1, 1956, or show that due diligence was being exercised to extinguish the fire.[45] The court found that the gentleman’s failure to extinguish the fire or show that he had diligently attempted to extinguish the fire after January 1, 1956, was a violation of the ordinance.[46] Additionally, the court held the following facts were immaterial in determining whether the gentleman had violated the ordinance: (1) he did not own the land in fee simple, (2) he did not create the GOB pile, and (3) he did not cause the fire.[47]

More recently, in 2005, the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit refused to hear a case regarding adverse effects resulting from a nearby GOB pile.[48] In Korte v. ExxonMobil Coal USA, Inc., Korte brought suit claiming that airborne dust from a nearby GOB pile resulted in “a mild obstructive lung problem including a small bronchospasm component.”[49] However, the court in this case never reached the merits of the claim because the doctor offered by the plaintiffs failed to qualify as an expert witness under the federal rules of evidence, and without the doctor’s testimony, the essential element of causation could not be proven.[50]

Impacts from unstable GOB piles (international incidents)

GOB piles vary widely in composition, size, and construction throughout the world and the United States.[51] Coal refuse can be “deposited by dump trucks, dropped from aerial trams, dumped from mine cars (where the tracks are laid on the pile) and deposited by conveyor belts” creating GOB piles.[52] These methods can affect the stability of piles and the rate of combustion within a pile.[53]

Although incidents involving GOB pile collapses are not as frequent as the claims of water and air pollution discussed throughout this report, the harm from such a collapse can be substantial. Consideration of the potential health and safety impacts of GOB piles must include a discussion of the 1966 “Aberfan disaster.”

The Aberfan disaster occurred in Aberfan, Wales, in 1966, and is likely the most significant incident resulting from faulty stability of GOB piles.[54] At this time, several GOB piles, known as tips, were built on the mountainside along streams situated above the village of Aberfan.[55] Tip 7 laid on “highly-porous sandstone riven with streams and underwater streams.”[56] In 1963, the tip slipped, trapping the mountain spring water within the tip.[57] Despite warnings from engineers and other concerned residents of Aberfan, nothing was done.[58] On October 21, 1966, after relentless rain for about a week, the tip slipped once again.[59] As a result of this small slip, 144,000 cubic yards of black slurry and coal refuse avalanched down the mountainside destroying farmhouses, a school, and cottages.[60] One-hundred forty-four lives were lost, 116 of which were children attending school.[61]

During this time, the United Kingdom and Aberfan had no laws or regulations governing mining and/or the creation and storage of GOB piles.[62] Well aware of the magnitude of the disaster, the government ordered an immediate inquiry, and, after 76 days, investigators deemed the National Coal Board (NCB), a statutorily created agency that took control over the country’s mines and operations, was responsible for the disaster.[63] However, the lack of rules and regulations allowed NCB to continue business without a significant punishment.[64] Since then, the United Kingdom has adopted the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act of 1969, giving details on the proper construction and inspection of GOB piles.[65] However, landslides have not stopped or been prevented. More recently, on February 12, 2013, a GOB pile landslide near Hatfield and Stainforth rail station in South Yorkshire resulted in a section of the railway being destroyed. While no one died in this accident, the railway was forced to shut down for some time.[66] No pending litigation could be found regarding this recent landslide.[67]

Economic Value of Improved Public Safety

The removal of coal refuse piles eliminates any possibility that they will catch fire in the future at that site, producing a quantifiable avoided fire response cost for the Commonwealth of Virginia. Depending on the size of the fire and other factors – location, access issues, etc. – the cost of extinguishing burning coal fires and securing the site can be significant. To date, at least $1.75 million in AML funding has been committed to extinguish and control surface coal fires in Virginia.[68] Recently reported projects in Pennsylvania regarding extinguishing coal pile fires suggest an average cleanup cost of approximately $120,000 per acre.[69]

Based on this benchmark and data on waste coal fire remediation efforts in Pennsylvania, an effective fire reduction rate is calculated utilizing the annual removal and remediation of waste coal. The removal of 400,000 tons of coal refuse annually reduces the expected fire response costs by $2,400 in year one. These benefits accumulate over time, because the fire risk is permanently removed when a site is remediated.

In addition to fire risks, piles are structurally unstable and can collapse, leading to landslides and mudslides that have affected public and private lands, including highways, homes, crops, and forests. Public safety issues are compounded by the number of coal refuse piles located in populated areas. Unfortunately, unsupervised piles are frequently used for recreational purposes, particularly all-terrain vehicle (ATV) and bike riding, activities that are not uncommon in southwest Virginia. Due to the instability of the piles and dangerous debris on the sites, this activity can lead to serious injury and even loss of life.

Benefits from avoided fatalities and injuries can be quantified based on government guidance on the statistical value of a life and varying degrees of injury commonly used in cost-benefit analyses. Based on the historic rate of annual fatalities and the established relationship between ATV deaths and injuries, the removal of 400,000 tons of coal refuse annually yields an avoided fatality and injury value of more than $32,000 in year one.[70] This amount grows over time as sites are remediated in future years.

Net Emissions

Legacy GOB piles generate emissions due to their contents. These emissions increase if the GOB is burned, either in an uncontrolled manner as piles catch on fire, or in a controlled setting using GOB as a fuel source for energy generation.

Burning piles create a range of uncontrolled negative atmospheric impacts, including smoke, minute dust particles, and the release of poisonous and noxious gases, including carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulfide, sulfur dioxide, ammonia, sulfur trioxide, sulfuric acid, and oxides of nitrogen.[71] These pollutants can be fatal to vegetative life and negatively impact human health. [72]

When GOB is used as a fuel source, emissions take place in a controlled and regulated setting. According to Dominion Energy, the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center (VCHEC) employs two fuel-flexible circulating fluidized bed boilers (CFB) [73] which are uniquely designed to burn coal, waste coal, and up to 20% biosolids[74] and serve as the plant’s engine, with an energy generating capacity of 585-MW.[75] In addition, the steam produced by the boilers powers a 668-MW steam turbine. The dual system incorporates advanced air quality control equipment comprised of a dry scrubber, baghouse particulate filter, selective noncatalytic reduction system, and an activated carbon injection system to reduce environmentally unfriendly materials such as mercury from entering the atmosphere.

The VCHEC also utilizes several water-saving design features, such as reusing the leachate derived from their solid waste storage facility for ash wetting and the system’s dry scrubber. Dominion reports that water usage at the VCHEC is roughly 90% less than the amount of what’s used at an ordinary facility. The facility also recycles heat from the CFB boiler system to preheat the feedwater, ultimately improving the overall plant heat rate.[76]

Even with the controls and environmental protections in place, the use of GOB as a fuel source still generates material carbon emissions. The VCHEC uses a blend of waste coal, coal, and other biosolids, meaning that its emissions profile is not representative solely of GOB-generated activity. Data from Dominion Energy indicates that GOB represents 27% of fuel utilized at the VCHEC from the opening of the plant in 2012 through August 2021. During this time, emissions from energy generation at the VCHEC totaled 25.5 million tons.[77]

The net emissions effect of using GOB as an energy source is difficult to quantify and depends heavily on how the “counterfactual,” in which GOB is not removed for this use, is defined.

For instance, it is not clear whether the marginal energy that is generated through waste coal would be replaced by a zero-emissions fuel source in the near term. Notably, the Virginia Clean Economy Act (VCEA) recognizes natural gas as a fuel source with an extended role in the transition of Virginia’s energy portfolio.[78] It may be that the alternative to burning waste coal for VCHEC’s energy generation is energy generated from a natural gas facility.

Data from the US Energy Administration shows that energy generation from natural gas has a smaller emissions footprint per kWh of energy generated than coal plants, and an emissions footprint less than half that of the VCHEC when running at capacity (see Figure 3.2.[79] The emissions profile for alternative energy generation is material in considering the net effects of emissions from GOB as a fuel source.

Additionally, the counterfactual must consider the effects of GOB pile emissions over time if they are left unremedied rather than used for energy generation. Passively, GOB coal piles release coal dust and particulate matter as it is loosened and swept up by the wind.[80] More seriously, piles can catch fire, leading to uncontrolled burning without any measures to capture or mitigate the release of traditional air pollutants. Burning coal in a GOB pile represents a more severe emissions scenario than the burning of waste coal in a controlled and equipped facility.[81]

While emissions from the use of GOB for energy generation are knowable, the level of averted emissions from alternative energy sources and from the remediation of piles and potential fires is not clearly defined. Net emissions are not considered directly within the economic framework in this study. Ultimately, decisions as to combusting waste coal are left to policy makers to determine whether the increased GHG emissions are worth the incentive of creating a market for GOB.

3.3. Reclamation of Land

The remediation of coal refuse piles also returns substantial areas to productive land use. Reclaimed land has become recreational parks and soccer fields, pastures, industrial parks, shopping centers, and housing developments, adding considerable value to private landholders and to the general public. On the other hand, coal refuse piles are frequently located in populated areas where they represent a drawback/disadvantage for nearby homes, reducing the quality of life and property values for residents.

As of January 2022, the home page of Virginia Energy’s website touts the innovative repurposing of the mined land in southwest Virginia. The site even links to a video of such efforts, explaining that “Virginia Energy has long been involved in economic development with a special focus on coal-impacted communities in southwest Virginia.”[82] The video explains how previously mined land is being repurposed to create new opportunities for jobs and the community.

Local Examples of Putting Reclaimed Land to Productive Use

Reclamation of AML sites is about remediating the environment, as well as creating value for an economic asset for the local community. Several outdoor recreation sites – Norton Riverwalk, Tipple Hill Park, Spearhead Trails, and Project Claim – all started with improving environmental quality and then repurposing or enhancing the site for its economic opportunities.

The Norton Riverwalk and Tipple Hill Park project successfully reclaimed the 11.1-acre site of a pre-1977 surface mining location. Remediation involved the mitigation of Acid Mine Drainage and the preparation of an environmental assessment. The project then conducted a full construction and design to improve the aesthetic assets for the local community, which was thought to have incentivized walk-up businesses to locate nearby.[83]

Spearhead Trails is an organization and a multi-trail network that crosses numerous AML sites in Tazewell County. Partnering with Pocahontas Land Corporation, it has successfully remediated and opened the Original Pocahontas (OP), generating approximately $1.5 million in new investment since the opening in 2014.[84] Located on a subsidence-prone, environmentally impaired area and next to two GOB piles, the land reclamation effort involved removal, hauling, and disposal of waste material to an off-site location, sealing portals, and designing for trail improvement and expansion. This effort was followed by the Pocahontas Exhibition Mine and Museum project, which benefited from AML Pilot Funding and further integrated the trail system into the local tourism economy.[85]

Project Reclaim[86] turned a 32-acre GOB pile and its adjacent lands into a regional industrial site in Russell County. After backfilling and grading the GOB pile, the project also identified and repurposed several infrastructures and utilities to support the industrial site, including existing rail siding, an electric distribution line, gravel roads, access points to bridges, water supply, natural gas, etc. Three industrial projects expressed interest in the site upon projected completion.

Both the reclamation of previously unusable land and the value impacts to nearby residents represent quantifiable economic benefits resulting from the industry’s remediation of coal refuse piles. These benefits accrue largely to private residents and local governments (which benefit from increased land value and the potential for commercial uses), rather than directly to the Commonwealth. Land value benefits resulting from the remediation of a site are one-time rather than cumulative benefits.[87]

Economic Value of Reclaimed Land

According to information provided by Dominion Energy, activity by the VCHEC has reclaimed roughly 1,700 acres of land since 2012, restoring it to productive use. Applying the historic relationship between beneficial ash utilization and reclamation to the recent annualized volume of ash reclamation, it is estimated that 189 acres are restored annually.

Using an assumed land value of $4,000 (based on pasture-land values in Virginia published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture), the annual benefit of this rehabilitation activity is estimated at more than $755,000.[88] This approach may be conservative, since land values for non-agricultural uses like those described above may be higher.

Remediation of GOB piles can also have positive effects for nearby properties. Incremental benefits to properties within one-quarter mile are estimated at 5 percent, the lower end of the range of statistical results for similar blighting influences, such as landfills.[89]

Several coal refuse piles are in proximity to developed areas and population centers. As detailed in Section 2 of this report, at least 115 piles are located within 10 miles of some of the densest population centers in southwest Virginia. This means that the blighting effect of these coal refuse piles apply in many instances to residential and commercial properties. This analysis conservatively continues to use an estimated land value of $4,000 per acre based on agricultural land values, consistent with the approach used for remediation and restoration of the piles themselves.[90]

Spatial analysis based on refuse pile sizes indicates that for each acre of coal refuse, there are approximately 16 acres of nearby property. Based on an assumed 5% blighted effect, the estimated increase in nearby property values from the remediation of 189 acres per year is estimated at $617,000 per year. These benefits would be shared among private and public landholders with property in proximity to existing GOB piles.

3.4. Summation of Environmental Impacts

To summarize the monetized value of the remediation and reclamation of GOB-affected areas over time, the categories of benefits described above are calculated annually over a 20-year period. Benefits from water quality and public safety accumulate over time, since remediated areas continue to deliver avoided costs in subsequent years, while benefits from land reclamation and nearby property value are treated as a one-time social benefit in the year in which they occur.[91]

As noted above, the full extent of GOB piles in Virginia in need of remediation is unknown. As a basis for the calculation, this study uses the annual level of remediation undertaken by the VCHEC, which is approximately 400,000 tons of GOB and 189 acres of land restoration annually.

Importantly, the quantification of benefits in this analysis is entirely forward-looking, in that future activity is designated as “year one,” and activity undertaken to date is excluded from the calculation. The accelerating benefits over time outlined below illustrate that recent remediation activities have delivered and will continue to deliver considerable value for Virginia.

Year 1 benefits from this level of GOB removal and remediation are estimated to total more than $1.6 million, with the majority derived from land reclamation and property value effects. Over time, water quality and public safety benefits, which compound annually as more coal refuse piles are remediated, begin to supply the majority of the benefits. Water quality benefits represent the largest category of savings over time, generating an average of $1.9 million in nominal benefits over the twenty-year horizon.

Total benefits accelerate from an estimated $1.6 million in year 1 to $5.6 million in year 20. Over the 20-year period, benefits total more than $77.6 million in nominal terms, averaging $3.9 million per year (see Figure 3.3).

This framework assumes the removal of 400,000 tons of GOB per year over a 20-year period, which is equivalent to the removal of 8 million tons. As discussed throughout this report, the total volume of legacy coal refuse piles in Virginia is unknown, but may be significantly larger than this figure. Optimistically, this means that Virginia could achieve proportionally larger benefits if a greater volume of GOB than this benchmark is remediated in the coming years. More pessimistically, the inverse is also true: failure to act and continue remediation efforts turn these benefits into liabilities. The damages that would be avoided through remediation are instead realized, and if the volume of legacy coal is indeed greater than the baseline put forward here, those damages will be commensurately larger than the impacts calculated here.

4. Remediating Virginia’s Legacy GOB Piles

This section considers potential options for remediating legacy GOB piles.

-

Section 4.1 discusses various remediation approaches, including leaving the piles in place. When leaving the piles in place, mitigation is needed through removing and better storing the waste coal or removing the waste coal and making economic use of it, such as generating energy.

-

Section 4.2 reviews the legal framework that governs GOB site remediation and related environmental issues, most notably the Surface Mine Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) and the Clean Water Act.

-

Section 4.3 considers Virginia’s regulatory environment, including its transition to a cleaner energy environment.

4.1 Potential Remediation Approaches

Legacy GOB piles produce several hazards to the environment and landscape, which are described in detail in Section 3 of this report. “Remediation” of these piles encompasses several potential strategies to mitigate their harmful impacts. Remediation is, thus, not a uniform activity and can be approached in different ways depending on the location, nature of the pile, available funding sources, intended land uses, and other specific factors.

This section seeks to outline the potential approaches that have been implemented in Virginia and elsewhere for the remediation of coal refuse piles. Broadly, there are two major approaches to GOB pile remediation:

-

remediation in place; and

-

removal and remediation.

Remediation in place efforts involve actions that mitigate the environmental harms from a GOB pile without the direct removal of the coal refuse. Techniques include grading and revegetating piles, and mitigation efforts for nearby waterways. These interventions are generally more cost-effective than removal approaches, but are typically partial solutions to the ultimate underlying environmental issues.

Remediation involving the removal of GOB requires coordination with multiple entities to transport the waste coal and provide a terminal location or use for that waste coal. Remediation and the subsequent removal are notably more expensive than remediation involving leaving the piles in place. These methods, however, necessarily remove the source of environmental damage, providing social and environmental benefits and the opportunity to recoup a portion of their costs. Generally, removal and remediation require the transfer of waste coal to a lined landfill site or used in one of a limited number of functions. As discussed, gaps in funding for lower-level abandoned mine sites, like GOB piles, create an economic advantage that generates enough revenue to facilitate thorough and complete remediation efforts.

The VCHEC’s energy generation provides one market approach that can help facilitate comprehensive removal and remediation efforts. As a generation plant capable of burning waste coal, the VCHEC can create a market for the extraction, transport, and use of GOB. This dynamic can be beneficial to remediation efforts, as the financial viability of using GOB as a fuel source leverages private funds, thereby making grant funding and public programs better utilized in remediation efforts. Through the energy generation process, the VCHEC generates coal ash; a byproduct of the burning process that can be used to aid in remediating GOB pile sites. Further, the avoided costs of lining and loading landfills, as well as the coal supplanted using waste coal, can both be considered tertiary benefits of burning waste coal for fuel.

On the other hand, there would also be environmental and social costs associated with combusting GOB at the VCHEC. The greenhouse gas emissions from the combustion of GOB would run contrary to current emission-reduction goals in Virginia and nationally. Such emissions would be exacerbated because as GOB is generally of lower quality, requiring more supplemental coal to achieve the same amount of thermal energy is necessary. This would also exacerbate the traditional air pollution associated with coal combustion. While coal ash may have some beneficial uses, it is a waste product that contains harmful contaminants that can pollute nearby waterways. Finally, while using GOB as a fuel source may extend the viability of the VCHEC, and, correspondingly slow the transition to a cleaner electricity portfolio.

Remediation in Place

GOB can be addressed on-site or off-site. When reclamation happens on-site, the approach involves stabilizing and covering the GOB with vegetative supporting material or species such as soil and beach grass. In addition, technicians manage existing water and soil pollution, implement hydrologic controls, and creates an ecosystem design for rehabilitation.[92] However, the treatment for pollution and land stability is hardly a one-time effort, and a healthy ecosystem takes years to be truly re-established.

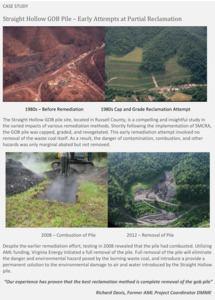

The legacy (pre-SMCRA) and post-SMCRA GOB piles scattered throughout southwest Virginia demand different levels of remediation efforts due to their creation and storage. Due to the lack of regulations present before the passing of SMCRA in 1977, coal mining companies typically piled refuse materials extremely high and abandoned them. This misguided approach makes the refuse materials prone to sliding. As a result, legacy piles often need to be reconfigured and stabilized before reclamation, causing them to be more expensive to remediate.[93]

A 2018 study by researchers at the Virginia Cooperative Extension at Virginia Tech University concluded that the “slope and aspect effects” of legacy piles in Virginia typically made them more challenging for revegetation and other typical mitigation measures.[94] The “uncompacted” nature of legacy piles also allows for more weatherization and oxidization, leading to higher rates of combustion and increased production of Acid Mine Drainage. [95]

Revegetation

The revegetation of GOB piles is a relatively straightforward, yet difficult process of waste coal remediation and reclamation. Several important factors must be considered to determine the best method of reinstating vegetation atop a GOB pile: soil pH, soil fertility, soil/refuse compaction, and soil gradient placement (based on the slope of the GOB pile).

Starting with soil pH, this measure provides active soil acidity and is typically the most used indicator of soil quality.[96] Depending on the mineral content of soil, the pH is subject to volatile fluctuations. For example, if the soil contains a majority of rock or similar materials, it is more likely to become acidic due to weatherization and oxidization. According to the International Journal of Soil, Sediment, and Water, “vegetation achieves optimal growth in the soil at a neutral pH.” [97] When soil pH drops below 5.5, it negatively affects the growth of legume and forage. As a result, low pH affects the ability of vegetation to establish roots within the soil. Conversely, soil with a pH of 6.0-7.5 is ideal for establishing vegetative growth.[98]

Mine soils usually require fertilizer to establish a vegetative ecosystem. Since coal refuse is comprised of weathered rock and coal fragments, there is generally a lack of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) available for plants.[99] However, due to the weatherable mineral content present in refuse piles, the piles typically provide sufficient levels of calcium, magnesium, and potassium for vegetative cover.[100] Therefore, it is imperative that fertilizer be added to account for the lack of nitrogen and phosphorus. Common forms of fertilizer used on refuse piles are biosolids or composts that help supply needed amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus.

Lastly, the compaction of soil, refuse, and the gradient of each are directly correlated. Starting with the former, dense soil poses a problem for several reasons. For example, it reduces the ability of plants to establish roots within the soil, leading to increased runoff and erosion; decreased water retention; and a lack of vegetative cover, which would ultimately increase the amount of AMD generated by the pile. Regulations requiring refuse material to be placed on a slope present a problem for the establishment of soil amendments on steep slopes without severe compaction. Further, the slope further exacerbates the issues associated with soil compaction.

Water Treatment (treatment plant, open limestone channels)

The two most common approaches to water quality issues caused by Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) from mine-affected sites fall under passive or active treatment. Typically, passive treatment is a less expensive approach to remediation as it only requires occasional maintenance, whereas active treatment requires more labor input and usually involves continuous reagent/chemical treatment over time.[101]

Importantly, while water treatment addresses the “symptoms” caused by GOB piles, it does not address the underlying cause. Water treatment can be strategically located to address runoff and other drainage generated by GOB piles. Economically, these efforts will be most feasible when used to aid in the remediation of several point sources or affected areas. Water treatment approaches are most effective in conjunction with efforts to deal with the GOB piles themselves.

A common but expensive approach to water reclamation is a water treatment plant. The award-winning computer-controlled Levels Road treatment plant, located in Powell, West Virginia, uses two two-channel ultrasonic flow meters, along with two 22-inch electric valves and two 12-inch electric valves to blend highly acidic refuse water with highly alkaline and calcium rich mine water. This process significantly reduces the cost of chemical inputs since the two water sources offset one another.[102] Alum, caustic soda, and flocculent are still added to the water as needed.

The computer system constantly monitors the flow from each pump and the electric valves open or close to adjust the blend ratio selected by the plant operator. The autonomous plant has been transforming the mine water (pH 6.4-6.7) and refuse water (pH 2.0-3.0) to a pH of 7.5-8.0 since its resurrection in 1999, winning the West Virginia Coal Association Reclamation award in 2000 and the West Virginia Business Environmental Leadership Award in 2002.[103]

Another less expensive form of water remediation involves open limestone channels (OLC). Open limestone channels are used to reduce the acidity of runoff as it descends from its originating location. In theory, the calcium carbonate (CaCO3) contained in the limestone dissolves the acidity in AMD-affected waters and increases its pH as it encounters the stones.[104]

The structure of OLCs is relatively simple, consisting of two common construction methods. The first is the construction of a drainage ditch that collects and drains water contaminated by AMD. The second requires placing limestone fragments directly in a contaminated stream.[105] The placement of limestone fragments is likely to represent a lower-cost option, since the primary costs are limestone and labor. The cost of implementing an OLC is relatively low compared to other methods. Costs generally associated with the construction of a drainage ditch consist of excavation, labor, and the acquisition of limestone. Dr. Paul Ziemkiewicz, director of West Virginia Water Research Institute at West Virginia University, puts the average cost of an OLC at $27,500.[106]

However, open limestone channels typically lose effectiveness over time since there is no protection against oxidization which causes metals to precipitate and, in turn, causes the limestones to become armored.[107] Armoring can be explained as the accumulation of precipitate on reactive surfaces acting as a chemical barrier reducing reactivity at the point of contact. To increase the effectiveness of OLCs, it is important to consider the slope of the channel and the rate at which water is passing since the slower AMD water passes through OCLs, the faster armoring occurs, and the water’s acidity (the same relationship discussed above can be said regarding the water’s acidity). On the other hand, the water must not travel too fast through the channel since it needs enough contact time for the reaction with CaCO3 to occur, and channels should be long enough to neutralize the acidity of the water by the time the channel ends. That said, titration studies comparing the effectiveness of armored limestone and unarmored limestone found that the former will still treat AMD, albeit less effectively than the latter.[108]

Removal and Remediation

An alternative approach to addressing GOB-affected areas involves the removal of waste coal and subsequent remediation of the site. GOB removed from a site can be permanently and safely stored at another location in a limited number of ways, primarily through specially lined landfills or repurposed mine lands. GOB can also be repurposed for uses, including as a fuel source for energy generation. The repurposing of GOB for economically productive uses can facilitate its removal and subsequent remediation.

Regardless of the destination or terminal use, removing the waste coal directly removes the underlying source of environmental damage. Thus, removal and remediation are the most complete option for addressing the environmental damages and hazards posed by GOB piles, relative to remediation-in-place efforts, which generally only mitigate environmental impacts partially or temporarily.

Removal and remediation approaches are notably more expensive than remediation in place efforts. The costs associated with transportation, preparing landfills or other destinations, and the costs and difficulty of coordinating with multiple entities, all create financial barriers to removing GOB from pile sites. The viability of each approach relies heavily on being able to coordinate among multiple entities to achieve the intended end use. If there is no viable use for the waste coal, the only removal option available is the permanent disposal of the coal, which carries significant costs for proper storage and maintenance. Disposal of waste coal has no direct economic product, meaning it does not generate any form of revenue to offset the associated costs.

If an appropriate end user for the waste coal can be identified, and relevant legal, regulatory, and financial issues are considered, waste coal removal and re-use are far more economical. By creating an end-use and revenue stream, transportation, coordination, and land reclamation costs can potentially be fully or partially offset.

Disposal Options (lined landfills, active mine sites)

Safe disposal of removed GOB that does not have an end use requires a location that is appropriately prepared to mitigate environmental damage. This typically entails either a lined landfill, or coordination with an active surface mining site that is taking measures to safely store newly generated coal refuse.

Landfilling is a common practice used to deal with hazardous waste materials. In the context of coal mining, landfills are commonly used to store combustible coal residuals (CCR), a byproduct of coal that has been burned to be converted into energy. There are several types of CCR, including fly ash, bottom ash, boiler slag, and flue gas desulfurization material, which can be collected and stored in a landfill. Similarly, waste coal can be stored similarly to CCR. The Environmental Protection Agency published its Final Rule on the storage of CCR on April 17, 2015, which provides rules and regulations for the storage of such materials. Based on the EPA’s Final Rule, there are five regulations that owners and operators must follow including location restrictions, liner design, structural requirements, operating criteria, and groundwater monitoring and corrective action:[109]

-

Location Restrictions: CCR landfills cannot be placed above uppermost aquifers, wetlands, within fault areas, unstable areas, or seismic zones.

-

Liner Design: criteria have been put in place to reduce the rate of leachate from waste which tends to affect surface and ground waters. Landfill liners must be composite liners made of a two-foot layer of soil and a geomembrane in direct contact with one another. New piles require additional protections in the form of collection/removal systems to deal with leachate generated and collected within the landfill, while existing piles (piles that formed before the EPA’s Final Rule) are only required to monitor the leachate and groundwater.

-

Structural Requirements: requirements apply to new and existing sites and require owners and operators to continuously assess landfills for slope stability continuously.

-

Operating Criteria: criteria are set by the EPA and consist of air criteria, run-on and run-off controls, hydrologic and hydraulic capacity requirements, and periodic inspection requirements to ensure the safety of owners and operators and to reduce the environmental impact of sites.

-

Groundwater Monitoring and Corrective Action: EPA regulations mandate the use of detection monitoring, assessment monitoring, and corrective action systems/procedures related to groundwater monitoring and corrective action.

Taking all factors into account, constructing and maintaining a landfill is a costly form of remediation. In addition, transportation costs often make the landfills economically unfeasible.

In some cases, it may be possible to coordinate safe disposal with an available nearby site. For example, in 2016, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) awarded a contract to Rosebud Mining Company for the removal, disposal, and rehabilitation of a 62-acre coal refuse pile in Ehrenfeld, Pennsylvania. The project used federal AML pilot funds at a bid of $13.5 million for removal and rehabilitation.[110] Including an additional $12.7 million for disposal of the material totaling $26.2 million for the project.

Importantly, Rosebud controlled disposal costs for this project by relocating the refuse (mixed with an alkali) to nearby strip-mining pits that it owned, limiting transportation and storage costs.[111] In announcing the award, DEP noted that previous bids – originally solicited in July 2013 – were cost-prohibitive until the identification of the nearby disposal location “resulted in a cost reduction to allow the contract to proceed.”[112] Rosebud’s bid reflected a cost of around $11 per ton – split roughly even between removal and disposal – as well as a rehabilitation cost of around $20,000 per acre. Pricing from three bidders in 2016 for removal and rehabilitation were 15 to 20 percent higher than Rosebud, at about $7.50 per ton for removal and $23,000 per acre for rehabilitation.

Cost differentials for disposal are far higher, with two competitive bids for disposal costs in 2013 averaging more than $25 per ton, more than four times the cost to Rosebud. This cost is likely more reflective of the typical cost profile that the state would incur for disposal, absent the unique circumstances of the Rosebud bid.

Beneficial Uses for Removed GOB (including electricity generation)

Alternatively, if an end-use can be found for GOB, storage costs can be eliminated, and revenue can be generated to support removal and remediation. GOB is most commonly utilized as a construction material or as a fuel source for energy generation.

GOB can be used as a construction material for area fill and structural support, similar to coal ash usage as a structural fill.[113] The Federal Highway Administration has pointed to burnt coarse coal refuse being suitable for embankment or fill material.[114] In addition, a study has shown waste coal can serve as a source for ceramic raw materials used in brick manufacturing.[115] Coal has also been studied as a potential component for plastic composite, potentially useful in applications such as plastic decking and similar construction.[116]

GOB was not considered a popular fuel source historically. Its low British Thermal Unit (BTU) brings a low unit value for power plants. However, in recent years, clean coal technology – such as the Circulating Fluidized Bed Combustion (CFBC) technology – has improved the technical feasibility of using GOB for energy generation. The VCHEC is a CFBC plant that turns both GOB and biomass from the regional reclamation activities into power for southwest Virginia.

The use of GOB as a fuel source for energy generation is part of a broader “fuel cycle” that can produce both revenue and byproducts to support the remediation of affected areas. A byproduct of the energy generation process is fly ash, which can be used as part of the remediation process to help neutralize acidic elements at the re-mining site (or elsewhere). The fuel cycle approach used by the VCHEC changes the economic structure of coal refuse pile reclamation by generating revenue to offset removal and transportation costs, generating a byproduct for use in remediation, and alleviating the need for disposal of unused coal refuse removed from the original site.

This model also introduces private sector resources to complement public sector investment. Total remediation of GOB coal in Virginia may not be completed through public funding and initiatives alone. To effectively address the issue, private investment may be necessary. This is precisely the nature of the VCHEC’s operations. Multiple projects have leveraged AML funding, and the removal and remediation efforts are carried out in coordination with Virginia Energy, which funds aspects of the remediation efforts.[117] The removal and remediation efforts that both the VCHEC and Savage conduct are a combination of public and private investment that Dominion claims follows regulatory guidance to appropriately use waste coal while remediating impacted Virginia land.

Further, there are additional uses for ash from burning GOB coal. In West Virginia, the Grant Town Power Plant reclaims substantial amounts of waste coal, consuming and removing more than 12 million tons since its first operation in 1993.[118] The ash generated from the Grant Town Power Plant was approved as a substitute for cement in concrete by the West Virginia Department of Highways.[119] This example demonstrates a potential downstream product chain of coal refuse economics beyond the common use of ash as a remediation material.

Importantly, this approach is unlikely to be a realistic option for all GOB piles in southwest Virginia due to logistical considerations. First, there are significant fixed costs associated with the re-mining process. Piles below a certain size likely do not provide a sufficient potential return from energy generation to justify these costs. Second, transportation of GOB once it has been removed represents a major component of the overall cost equation. This transportation cost is partly a function of distance to the VCHEC, which is in a fixed location. Those piles that are located further from the facility are progressively less cost-feasible to use for energy generation at the VCHEC. Transportation of waste coal will also trigger environmental concerns relating to coal dust.

Figure 4.1 shows the distribution of known GOB piles by distance from the VCHEC. While the feasibility of any pile as a fuel source for the VCHEC depends on multiple factors, piles further than 45 miles from the facility have prohibitively high transportation costs. These piles are generally considered infeasible as fuel sources for the VCHEC.[120] Closer, smaller piles are also likely infeasible as fuel sources for the VCHEC due to the fixed costs associated with removal and remediation efforts.

Challenges such as these highlight the importance of individual site analyses in determining the most appropriate remediation strategy.

4.2. Legal Considerations for Remediation

Virginia and Congress maintain a strong legal framework for conducting responsible GOB pile remediation. This section outlines the legal landscape within which a systematic effort to reclaim GOB piles in southwest Virginia would operate. GOB pile remediation would have to comply with certain federal laws, including the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (SMCRA), the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the Clean Water Act. This section describes each of these federal programs, how Virginia operates as a regulator, and how these broad programs may affect GOB pile reclamation efforts.

Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (SMCRA)

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (SMCRA) provided a comprehensive federal framework of environmental regulations that govern coal mining on the surface of lands within the United States.[121] In 1977, Congress determined that surface coal mining caused severe erosion; contributed to flooding; polluted waterways; and generally degraded land in ways that harmed habitat, commerce, agriculture, and communities.[122] However, Congress also identified the expanding national need for coal as an energy source requiring an urgent need to establish standards addressing the effects of surface coal mining on public health.[123] Thus, Congress established SMCRA, a regulatory process to prevent, account for, and remediate damage to land caused by surface coal mines.[124] Additionally, Congress sought to remediate the historic accumulation of mining waste and lands rendered unusable by surface mining.[125] The purposes of SMCRA are diverse and enumerated in 30 U.S.C. § 1202.[126]

Congress observed that coal mining before 1977 left behind a substantial amount of unreclaimed land that imposed social and economic costs onto communities near those sites.[127] Within SMCRA, Congress addressed the environmental risks of surface coal mining through Title IV and Title V. Title IV of SMCRA established the Abandoned Mine Land Reclamation Fund (AML Fund) and authorized reclamation of historic, pre-1977, coal mining.[128] Under Title V of SMCRA, Congress established a complex set of requirements that apply to post-1977 mining and protect, manage, and restore lands impacted during and after coal mining.[129]