The world experienced and continues to experience the detrimental effects of the COVID-19 virus regarding employment, health, social norms, and public education. In my lifetime, no health crisis has more affected day-to-day life than COVID-19. Specifically, COVID-19 and the virus’s spread forced my private law school to move to online learning for the remainder of the spring 2020 semester, followed by other later changes. Given the novelty of certain methods of instruction that resulted from COVID-19 and the quarantine period that ensued, it would be difficult for any student to easily adjust to the changing educational landscape.

COVID-19 also changed how teachers and instructors deliver lessons to their students and how students learn outside of the physical classroom. Considering that almost all public schools were moved online because of the Nation’s shutdown, a majority of students had to rely on their financial resources to access education. Thus, a student’s home environment is critical in receiving a quality education during a pandemic, but the school district influences how and if remote learning is delivered. Both today and as it existed before COVID-19, one’s education is largely influenced by their family’s resources and the school district they live in. Ultimately, it is the manner of funding public schools receive from their local and state’s governments that determines the quality of a child’s education, which creates a system that does not offer equal education to all. Until the Constitution recognizes education as a fundamental right, public school funding remains inequitable. This situation, exacerbated by the pandemic, demands the revision of how and to what extent we finance local public schools.

In this article, I will primarily focus on K-12 education in public schools, how those schools are funded, and the public school system’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Part I will focus on Virginia’s property tax system, which impacts how and to what extent public schools are funded at the local level, and the impact this system of taxation has on the quality of education offered by a particular school district. Part II will discuss the imposition of state-mandated policies in response to the COVID outbreak, including state social distancing policies, state shutdowns, and the effects of COVID on public schools. Part III analyzes the transition to online learning in various localities and how families and public schools responded to learning outside the physical classroom. Many students, parents, and teachers faced tremendous difficulties during the shutdown, and certain inequities among rural and suburban school districts were made clear as a result of the required movement to virtual learning. Finally, Part IV will focus on the lasting effects of online learning in public education as a whole and the potential alternatives to address inequitable school funding issues exposed during COVID-19.

I. The Property Tax System

Education is not considered a fundamental right despite the importance of education and its instrumental role in our Nation’s society. Thus, an individual is not entitled to have equal access to or an equal opportunity to education.[1] This controlling principle was challenged by the petitioners in San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, where the Court ultimately held that the school funding system in Texas was not unconstitutional because it did not discriminate against a suspect class and that education is not a fundamental right.[2] Local property taxes largely financed Texas school districts that allegedly created inequitable educational opportunities. [3]

Public education is funded by federal, state, and local governments.[4] However, federal funding is often limited, leaving state and local governments to bear the burden of financing public schools.[5] Funding for United States public schools is derived from three sources: local money, state money, and federal funds. For example, a typical funding arrangement would be 45% local money, 45% from state, and 10% from federal funds.[6] With the exception of Hawaii, every state’s public education system relies on the taxes collected within the prospective school districts for financing.[7] As a result, the value of real property within a given school district is directly related to the amount of revenue that school district can generate.[8] Consequently, this method of school funding invariably leads to the same outcome, that those living in poorer school districts will have access to a lower quality education compared to their wealthier counterparts.

In Burruss v. Wilkerson, a group of school-aged children challenged the Virginia Basic State School Aid Fund Act as unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause, an Act that apportioned state funds to local school districts.[9] The plaintiffs argued that the allocation of the state funds did not address the individual needs of the school districts and did not aim to accomplish equal opportunity among the different schools. Ultimately, the Court found no discrimination by the state and attributed the funding issue to the lack of “taxable values” to produce the money needed.[10] Thus, the U.S. District Court in Burruss reaffirmed the overarching principle of public-school funding, that local property values are the paramount factor in determining the quality of education within any given school district.

A. Virginia’s Constitution and Education

The Commonwealth provides for the funding of public schools through the provisions of Article VIII, § 1 and 2 of its Constitution. According to § 1, “[t]he General Assembly shall provide for a system of free public elementary and secondary schools for all children of school age throughout the Commonwealth, and shall seek to ensure that an educational program of high quality is established and continually maintained.”[11] On the other hand, § 2 states that “[t]he General Assembly shall determine the manner in which funds are to be provided for the cost of maintaining an educational program meeting the prescribed standards of quality, and shall provide for the apportionment of the cost of such program between the Commonwealth and the local units of government comprising such school divisions. Each unit of local government shall provide its portion of such cost by local taxes or from other available funds.”[12] Basically, § 1 established a free public education and aimed to provide all students with a high-quality educational program; however, this objective became merely aspirational, and most efforts cease upon reaching the bare minimum standards of quality. Whereas § 2 determined the amount of funds a school division received to meet § 1’s requirements, as well as the way in which local governments fund public schools.

Regardless of the importance of education and The United States Supreme Court’s acknowledgment of it as “perhaps the most important function of the state and local governments,” it is not a fundamental right under the federal Constitution.[13] Thus, because it is not a fundamental right under the U.S. Constitution, education does not have to be offered or provided equally to all children.[14] This inequality is evidenced by the different amounts of funding school systems generate across the Commonwealth, whereby schools in Northern Virginia exceed the educational standards of quality and those in the less affluent areas of the state struggle in meeting the minimum standards because of local property values.[15]

Despite relatively high property values, compared to other states, and a median income value per household in Virginia of $76,456, Virginia is 41st among state per-pupil funding.[16] In Virginia today, where a student lives determines their academic success and access to educational resources.[17] Virginia’s reliance on local governments for funding, more so than other states and the inequities in local property taxes, exacerbate the differences in school quality.[18] Virginia schools located in rural areas are more likely to have a significant percentage of their school-age population living in poverty, resulting in a diminished investment in their public schools and fewer resources for the students.[19] Ultimately because of this type of school funding inequality, certain constitutional challenges regarding one’s opportunity to receive an equal education as compared to other students have been made in the state courts, as occurred in the case infra.

B. Scott v. Commonwealth

A group of students and school boards brought suit for a declaratory judgment to find that Virginia’s system of funding public schools violated the Virginia Constitution.[20] They alleged that the Constitutional violation resulted from the funding system because it failed to provide an educational opportunity similar to those students from wealthier school districts.[21] The defendants (Commonwealth), filed a motion to dismiss, arguing that “substantially equal spending and instructional resources in [all] of the . . . school divisions . . . is not mandated by Virginia’s Constitution.”[22] The Trial Court held in favor of the defendants, finding that the Virginia Constitution only requires meeting minimum educational standards and not equal funding of the school districts.[23] Consequently, the plaintiffs appealed the Trial Court’s judgment and the Virginia Supreme Court reviewed the lower court’s decision.[24]

Virginia’s system of funding public schools is composed of (1) state and local funds mandated by the state aid system, and (2) local funds that are not mandated by the state.[25] The former is responsible for meeting the minimal educational standards aforementioned above, including instructional and support costs that are required by every school district.[26] The Board of Education is authorized to determine the standards of quality, while the General Assembly can make any changes prior to its finalization.[27] When comparing the wealthier school districts to lower-income school districts, the annual teacher salary was 39% higher in the wealthier districts and the wealthier districts always had a higher instructional personnel/pupil ratio.[28] The state and some school districts spent 2.5 times more money per child compared to others, for example, instructional materials’ costs ranged from $17.52 per pupil to almost $208 per pupil.[29]

Nevertheless, Virginia’s Constitution does not demand equal or substantially equal funding by each school division, but only guarantees that the General Assembly provide free public schools and meet the minimum standards of quality.[30] Although the Supreme Court affirmed the Trial Court’s ruling that public education is a fundamental right under Virginia’s Constitution, the funding system does not violate the Constitution because equal funding across school districts is not a constitutional right.[31] Ultimately, the Scott case reinforced the idea that the state cannot be found to have deprived students of any constitutional right merely because a wealthier school district has more funds than a poorer school district.

II. The Onset of COVID-19 and the Nation’s Response

On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a “public health emergency of international concern.”[32] However, it was not until March 2020 that the novel COVID-19 forced a majority of the United States to go into lockdown.[33] By March 17, 2020, all but two states had declared a state of emergency and by April 7, 2020, 42 state governors issued stay-at-home orders.[34] In further response to COVID-19, the states closed their economies, implemented social distance policies, and enforced mask mandates.[35]

Significantly, on March 16, 2020, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam ordered Virginia state schools to be closed from March 16-27.[36] Governor Northam closed the schools in response to the COVID-19 outbreak and stated that he would reevaluate future safety protocols at a later day. Unsurprisingly, on March 23, 2020, Governor Northam ordered all K-12 public schools to remain closed for the rest of the academic year.[37] The State tasked local school divisions with deciding how to move forward with educational instruction after closing the schools. Part of each division’s decision was how to complete the unfinished material for the year.[38] It is with this uncertainty and the divergent approaches used to address COVID-19, that students across the state and country received different methods of instruction.

There is no doubt that the United States and its public school system were ill-prepared to respond to a global pandemic. While the virus’s spread and the accurate dissemination of information about COVID-19 were a national concern, what to do in response to the virus was left mainly to the states.[39] By leaving it up to the states to take precautionary measures to address COVID-19, the pandemic created a path for legislatures and governors to wield their power over students and their families.[40] It was stated -in regard to the various approaches to the pandemic, “[w]ithout national guidance, the resulting disparities in actions by governors has created dramatically different impacts on students.”[41] Further, the only federal aid provided by Congress during the pandemic is from the Coronavirus, Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (“CARES”) Act. The CARES Act provided financial support for K-12 schools to adopt response plans to COVID-19 and meet the needs of their particular school district.[42] Although the act provided an Education Stabilization Fund of over 30 billion dollars, those funds were apportioned among K-12 public schools, higher education (colleges, trade schools, and universities), and non-public schools.[43]

Considering the lack of a uniform federal response to the shutdown of public schools and the diverse approaches taken by state governments, the results of COVID-19 on education varied. Essentially, the success or failure of virtual learning and the fulfillment of student objectives depended on the school district where one lived. In addressing this disparity, new pandemic school policies had a detrimental impact on lower-income students by exacerbating pre-existing opportunity gaps in the education system.[44] The combination of how public schools gain funding and the closure of schools due to COVID-19 are interrelated in that any given school district’s shift to online learning, ultimately relies on the amount of funding that school district receives. Finally, those schools with greater funding had better access to online learning, and those schools tended to have families that were able to stay at home with their children and provide childcare similar to that of schools.

III. The Transition to Online Learning

A. Life at Home and the Family

Other than the implementation of public school systems, the state provides minimal support to families and children.[45] Thus, the states have relinquished much of their responsibility in education and depend on local school districts and parents to provide the needed support.[46] The public school system functions by keeping children attended to, educated, and taught societal values. Additionally, schools serve a crucial role in the childcare system, which allows parents and caregivers to work during the weekday.[47] COVID-19 brought to light the State’s failure to provide for child care outside of schools, with the responsibility is left to parents and families despite their work schedules.[48] Due to the school closures, parents took on the additional role of being an educator.

Although some children are privileged enough to have adult supervision throughout the workweek, this is not the case for many American families. For example, an Atlanta Public Schools Superintendent decided to make home visits to students, regardless of whether or not they had been regularly attending class online.[49] The purpose of the home visit was to discover the reasons why the student may or may not be attending class, but more importantly to check in on the family.[50] A national survey reported that nearly half of parents with children in K-12 public schools were concerned about managing their responsibilities (work, childcare, the child’s education) at home.[51]

While internet access is a serious issue for many students, especially those in rural areas, so too is the availability of a caregiver who can assist the student.[52] One teacher from a rural area stated, “I think the reality that we’re dealing with in a lot of our communities is that our kids don’t have anybody at home to be able to help them during this time.”[53] While a majority of parents cannot work remotely, a Census Bureau report found that “[a]round one in five (18.2%) of working-age adults said the reason they were not working was because COVID-19 disrupted their childcare arrangements.”[54] Even the provision of online learning and technological devices does not solve the issue of child care during a pandemic, leaving parents in rural areas to choose between employment and unemployment.[55]

Owing to the concept of family life in the U.S. Constitution, the freedom from state intervention, the family is responsible for childcare.[56] This concept granted the State’s authority to shift responsibilities to the family and hold the family accountable for matters beyond its control (outside of school). Practically all children across the country experienced school shutdowns, and in Virginia, students were moved online for the remainder of the 2020 school year. By the end of March 2020, 50.8 million students were affected by school closures, and all fifty states either mandated or recommended schools be closed.[57]

Today, the troubles of COVID-19 reflect the pre-existing social inequality that persists in our society in regards to a student’s home life and how that student’s home life has a significant impact on their ability to obtain a quality education during the pandemic.[58] For instance, “[e]ducation law and policy, however, have also followed a trend of increasing risk for individuals, shifting responsibility for education quality and outcomes to parents, who then manage that risk in ways that shift it from the most to the least secure individuals.”[59] In other words, the educational risk is more about how families handle the shortcomings of public education, given that the state has relinquished much of its responsibility.[60] Thus, a student’s ability to receive an education during the COVID-19 era of school closures largely depended on the resources that were available at home.

B. Unequal Access to Technology

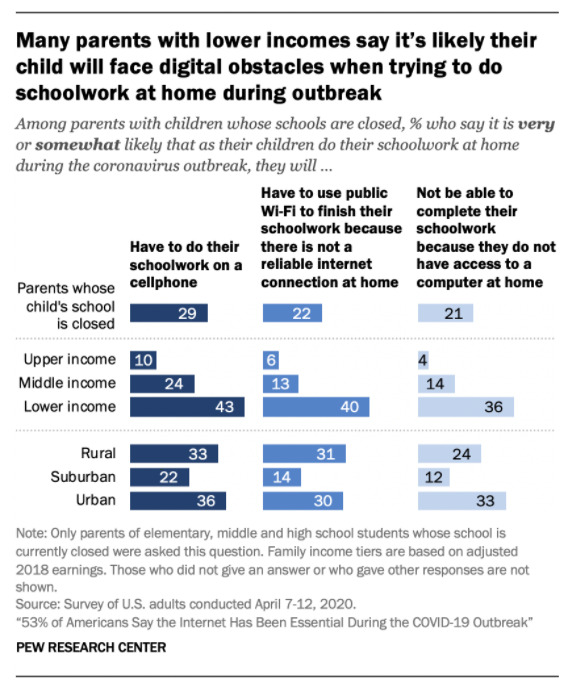

Alarming but real enough, an estimated 15% of over 50 million students in the United States today live in homes without access to high-speed internet.[61] According to a Pew Research Study, 36% of low-income parents reported that their children did not have access to a computer at home and could not complete schoolwork.[62] Comparatively, middle-class parents reported only 14% and upper-income parents 4%.[63] Consider, for example, a student that does not have access to the internet in their home; how will he/she be able to attend class via online learning? There are complications with this type of instruction because it requires families to provide resources that they would not need if there were in-person learning.

In particular, students with a low income and rural background suffered from the COVID-19 shutdown and struggled to participate in online learning compared to wealthier suburban students.[64] According to a study from 2019, 63% of rural adults are home broadband users compared to 79% of adults in suburban areas.[65] Additionally, those adults earning below $30,000 a year are only 56% likely to have broadband access, whereas those earning between $30,000 and $50,000 have a 72% likelihood.[66] Many students had no choice but to go without educational instruction if their families could not individually afford the virtual learning resources, or their school district could not supply these resources to their students. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics revealed that 14% of K-12 students did not have access to the internet while learning from home, and 17% of K-12 students did not have access to computers in their homes.[67] Therefore, access to education largely depended on access to internet and technology, something not all students are fortunate to have in their homes or provided for by their schools.[68]

What is referred to as the “digital divide,” essentially means the difference in access to the internet and other technological devices for students.[69] Unsurprisingly, the digital divide had a significant impact on students living in rural communities, with 37% of rural students that lacked adequate connectivity.[70] The National Education Association President said, “the level of poverty in a school is 'directly related to the success level of remote learning.”[71] I mean the deduction is fairly simple, those with higher incomes will be far more likely than those with lower incomes to access: the internet, laptops, computers, iPads, Google Chromebooks, video cameras, etc. Further, those higher-income families are more likely to live in suburban school districts that receive more funding, resulting in a situation where wealthier school districts have additional resources to provide for their students during school closures. For instance, less than a third of school districts included mobile broadband hotspots for their students as a result of school closures, with urban districts being two times as likely to receive the hotspots compared to rural districts.[72] With regard to the distribution of internet devices by half of the Nation’s school districts, urban and suburban districts were far more likely (84.6% and 59.1%) to reach their students than rural districts (43.2%).[73]

A survey from the Pew Research Center in April 2020, found that one in five parents believed it to be more likely than not that their children would be unable to complete their school assignments.[74] The parents’ answers were based on the inability of their family to access technology, despite that their school district implemented digital learning.[75] Thus, many students did not participate in online learning, as Bellwether Education Partners estimated that 3 million students had been absent from class since March 2020.[76] Contrary to a regular school year, parents and schools attempted to make technological devices readily available for virtual learning. Addressing the capability aspect of online learning, schools across the country took divergent approaches on supplying students with educational resources, but as always, the amount of money within that school district was enormously influential. However, not only did the amount of funding a school district received affect the access to online learning, but so did the geographical location of the school.[77]

In hopes of alleviating some of the issues in accessing and performing coursework, some school districts physically distributed materials and others utilized online learning.[78] Would you care to guess which school districts used physical materials such as handouts and packets? The lower-income districts. Studies showed that 47% of higher poverty districts adopted this practice.[79] Evidently, rural areas were far more likely to physically distribute schoolwork compared to their urban counterparts because rural areas tend to have less access to internet, technology, and economic opportunity.[80] Comparing both digital and classroom learning, teachers claimed that the biggest challenges were the lack of real-time feedback and determining whether or not students understood the material.[81] However, if those schools districts that implemented online learning feared a lack of real-time engagement, there is no doubt that those schools that used physical handouts could not adequately measure their students’ performance. Furthermore, rural school districts were less likely to expect their teachers to provide any instruction while schools were closed.[82] This is not to say that public school teachers in rural areas are less capable or worse than those in urban areas, but the average teacher salary in any given school district is related to school funding.[83] Thus, those students in impoverished rural areas that lack the resources at home and are in most need of highly qualified and experienced teachers, often face the reality that wealthier school districts pay their teachers more and can readily acquire the best teachers.[84]

Rural areas have their unique problems compared to suburban areas. Regarding public school districts, rural areas are far less equipped to distribute internet devices, ensure WIFI or internet access, prepare teachers for online instruction, and mark attendance. According to a survey of teachers, 75% of those stated that, “students’ lack of access to technological tools . . . and students’ lack of access to high-speed internet” is a grave challenge to online learning.[85] This is not to assert that families in rural areas are less likely to have internet in their homes, which may indeed be true, but rather it is more difficult to maintain a stable internet connection or access computerized devices for rural students.[86] For example, let us compare two school districts that I live in throughout the calendar year, and the amount of money that district spent per student in the fiscal year of 2013.[87] Warren County School District spent $7,764 per student compared to Buchanan County, which spent $15,115 per student.[88] Although it may appear that since Buchanan County Schools spent more money per student, their access to online learning should be greater than Warren County Schools; however, this is not the case. The important differences are the access to stable internet connection and availability of technological devices, resources that students in Buchanan County are less likely to have given that it is a rural and lower-income area.

According to the April Pew survey, nearly half of all parents with lower incomes said it would be very likely or somewhat likely (43%) their children would have to do schoolwork on a cell phone.[89] Forty percent reported the same likelihood of their child having to use public Wi-Fi to finish schoolwork because of an unstable internet connection at home, and around one third (36 percent) say it is at least somewhat likely their children will not be able to complete schoolwork because they do not have access to a computer at home.[90] Attached below is a survey taken from parents with children in public schools that were closed, showing the different responses based on their geographic location and economic background.

As seen from the chart above, the lower the parents’ income, the more likely the student would run into difficulties with schoolwork at home.[91] Worthy of mention however are the percentages for parents living in rural areas. At first blush, although the urban students seem as disadvantaged, if not more so, than the rural students, I am not convinced that is the case. While urban students are more likely to do their schoolwork from a cellphone, this does not account for the rural students that have cellphone access but do not have cellphone service.[92] Without service or a steady internet connection, no cellphone will be of any help for school. Even with cellphone access, a cellphone is not considered an adequate learning device for online learning given its disadvantages and distractions.[93] In terms of accessibility and connectivity issues with highspeed internet, high income, low income, and different education levels shared the concerns of rural adults.[94] Thus, educational funding is not the only factor that contributes to ongoing inequality in school districts, but rather more concerning is that not every student has access to high-speed internet at home.[95]

Although disappointing, the fact that those students in dire need of computers and the internet have not received aid from external sources is not a surprise.[96] Despite the United States offering all free public education, the Constitution lacks a right to equal education. As more time passes, our Nation feels the deeper consequences of COVID-19 on education and how unequal our system of funding public education truly is about student opportunity. Internet and technological devices have become synonymous with one’s physical presence in the classroom and participation in-class activities.[97] However, not all students can access the resources that are required for virtual learning, leading to either chronic absences online or the distribution of physical coursework. Considering the live instruction aspect of virtual learning, the greater percentage of low-income students within a school district leads to a lesser chance of that district providing synchronous classes.[98] Synchronous classes are those in which students may interact with other students and their teachers through live instruction, a staple of in-person learning.[99]

Not only were school districts with a greater percentage of low-income students less likely to offer online learning opportunities, but those rural school districts were also less likely to offer online learning than other geographical areas.[100] Below half of the leaders from rural and low-income school districts stated they were able to provide online learning opportunities compared to an upward 62% of suburban district leaders and 73% of districts with the fewest low-income students.[101] In particular, rural districts were even more disadvantaged because of their lack of technological expertise and infrastructure to make online learning happen, including the typical connection issues faced in those areas.[102]

As a result, rural schools districts utilized in-person handouts (41% of rural families and 22% of suburban families) as opposed to returning their students’ work online.[103] Clearly, rural teachers were more likely to provide their students coursework in person than urban or suburban teachers.[104] The issues that result from utilizing physical copies of coursework may include failure to track participation, delayed feedback, and the lack of one-on-one teacher-student instruction. Troubling to say the least, rural school districts had to overcome learning challenges more frequently than other school districts, even though COVID-19 has been burdensome on the entire population.

This note is not intended to bash rural communities or those who reside within them. I grew up in a small rural town and attend law school in the heart of coal mining Appalachia, so I know the struggles rural areas face. However, this note questions the purpose behind the Nation’s system of funding public schools and its controversial outcomes. Naturally, public school funding makes it more difficult for those residing in rural and low-income areas to break out of their environment. As digital technology becomes more commonplace in the workforce and education, the lack of universal broadband access in rural areas leaves those without internet worse off.[105]

Instead of establishing a funding system that would benefit those in the most need, America continues to rely on a system that further widens the achievement gap. Rather than render increased aid/resources to school districts that maintain the lowest property values and academic performance rates, our country still has made no effort to modify this outdated system. In the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education, Chief Justice Warren stated, “[i]t is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be available to all on equal terms.”[106] Today, denial of access to broadband internet and technology not only deprives a student the opportunity of an education, but rather an adequate education given the increased role both play in professional life.[107] Even though future plaintiffs attempted to use the language in Brown to challenge the unequal funding of United States’ public schools, they failed over and over again.

Although when students returned to the classroom, their schools were still unequal in terms of the school’s quality, 99% of public schools have broadband internet.[108] However, when students are required to stay home and access school material online, this leads to far greater inequality in internet access. Indeed not all people have internet at home, but “the shift to remote learning as COVID-19 hit the United States exposed the reality that reliable broadband internet now not only enhances traditional learning but simply enables basic instruction.”[109] Meanwhile, 58% of rural residents are likely to have high-speed internet at home, compared to 70% of suburban residents and 67% of urban residents.[110] Not only are rural areas less likely to have high-speed internet in their homes, but they too are less likely to use the internet and own mobile devices.[111] The so-called “homework gap,” the difficulty students experience with homework at home due to lack of internet compared to those who have internet, now not only involves homework but attending class.[112] Furthermore, these rural students lag behind their peers in terms of how to use technology, and must deal with the stress that is caused by numerous attempts to complete internet-based work from home.[113]

IV. The Consequences of Virtual Learning on the Return to the Classroom and Potential Solutions to the Inequality of Education

The challenges imposed on students’ ability to access virtual learning will lead to setbacks in academic success.[114] Caused by both absences and being outside of a classroom setting, studies show that upon return to school, there will be an estimated 30% reduction in reading levels and a 50% decline in mathematics.[115] Another study showed that on average students are five months behind in mathematics and four months behind on reading for the 2020-2021 academic year.[116]

The effect of school closures led some students to have gone “missing,” meaning the students either left that particular school system or failed to attend school at all.[117] Plenty of students that went missing did not regularly log on for virtual classes and failed to complete online assignments.[118] As online platforms continue to fall short of consistent and satisfactory student engagement, those unaccounted for students will suffer in the long term both academically and even in the job market. For instance, the pandemic left low-income schools seven months behind their learning goals, including high school students that had a higher dropout rate and fewer students attend postsecondary education.[119] By the time these underprivileged students reach adulthood and if unfinished learning remains unresolved, they are at risk of earning $49,000-$61,000 less over their adult life because of the challenges imposed by COVID-19.[120] The phrase “unfinished learning,” refers to students’ inability to complete all the learning and coursework they would have in a pre-pandemic world.[121]

This article does not suggest that the solution should be to reopen schools and get up to schedule with any lost learning but to develop a future educational funding system that offers equitable opportunities for all.[122] Clearly, the pandemic’s effect on public schools has exposed the unequal access to internet and technology, but more startling is without further action the current achievement gap will continue to grow.[123] Thus, COVID-19 has left the federal and state governments with no other choice but to reassess funding formulas, supplementary aid, and create plans that minimize the marked differences in public school funding.

The disparity among school districts and local tax values is nothing new to most Americans but rather an education system rooted in tradition. Nonetheless, COVID-19 has brought to the attention of many, including myself, that this is a serious issue that needs to be addressed by the legislature or the judiciary. Either through implementing a stimulus bill, the revision of public-school funding as a whole (by the Department of Education), or by challenging the constitutionality of the inequitable funding of schools for failing to meet minimum education standards, there needs to be redress for those deprived students. First and foremost, broadband internet is critical in modern society, and rural areas are far less likely than other areas to connect to high-speed internet.[124] Rural school districts are disadvantaged because they not only lack the resources to supply broadband to all students, but rural families have less access to broadband than suburban and urban families.[125] Thus, rural schools cannot provide rural students with the same lessons that urban schools can provide their students, leading urban students to have more opportunities and access to higher quality education.[126]

For these reasons, the Government must reinvent a public-school funding system which gives all students access to broadband internet. The legislature is best suited to create this new system because Congress is responsible for funding public schools at the federal level, and state legislatures (Virginia’s General Assembly) are responsible at the state level. Congress should take the necessary steps to prevent the growing digital divide among the Nation’s students and could do so by recreating an act like that of the CARES Act. Instead of distributing stimulus checks to federal inmates, large corporations, and persons that did not suffer a loss of employment or change in income, a large portion of that money should have gone to students that could not access online learning. This statement is not to say that stimulus checks were not helpful or necessary for those that needed them. However, eligibility requirements such as if one is single and make below $99,000 a year and a married couple that makes below $198,000 led to some beneficiaries that could have done without.[127] The handling of COVID-19 through the CARES Act could have been better suited to address the needs of students during school closures, rather than the allocation of funds to financially stable adults.

Although Congress could have tailored the CARES Act to the needs of public-school students, Congress could make this change to fund public schools. Today, there is no reason why some students should not have access to the internet and online learning, given that COVID-19 still operates against classroom instruction and the importance that this technology has in our society. While some schools can generate large amounts of funding solely from local taxes, other school districts fall short of those wealthier ones even with the combination of state, local, and federal funds. Even if the State gave more money per student to a specific school district it would not help. Each district is primarily funded by their local taxes and State funds only offset the district’s budget, so the low-income areas would still receive less funding.[128]

Therefore, to create a more equal, higher quality, and more productive education system, the State should direct funds for internet and technology devices to rural and impoverished areas. The wealthier school districts with advanced resources and more qualified teachers should not accept funds from the federal government, for they already provide their students with an adequate education. Additionally, the State should limit the funds given to school districts that benefit from local revenue excess. Rural and poorer school districts would benefit from the reallocation of the funds to their school districts. However, Virginia has adopted a method of funding similar to the one aforementioned, resulting in more funding from the State per student for those less wealthy school districts.[129] Despite this funding formula, the large amount of local funding received by wealthier districts outweighs any methods to achieve more state funding for poorer districts.[130] For example, one study showed that Virginia school districts with the fewest amount of children living in poverty still received 7% more state and local funding per student.[131]

Finally, the American Dream promises equality of opportunity for every American, which allows Americans to achieve the highest aspirations and goals. However, this dream is not feasible if the resources and opportunities provided by the Nation’s public schools are so different that some students can attend class online, while others are left to complete a physical packet by a certain deadline. Considering that COVID-19 is still a serious ongoing issue in this country, it is almost certainly there will be future school closures, and education will continue to move online because of its utility and convenience.

At a bare minimum, all students across the Commonwealth of Virginia and the United States should have access to the internet. Indeed, this would not completely solve the problem of the inequity in funding among school districts regarding facilities, teachers, courses, equipment, and all the other services/resources public schools provide. However, every student’s ability to access the internet would be a step towards what the Brown court envisioned, an opportunity for an education that is available to all on equal terms.[132] Providing the internet and a technology device would function as an equalizing force because they give students access to school and a vast amount of information and knowledge. The internet is an indispensable tool in modern society, and the public school system can better alleviate the unequal opportunities offered by its schools through universal access to the internet. Some schools have distributed internet equipment such as “Mi-fi devices,” that offer broadband connectivity to families that are unable to access online learning.[133] Additionally, other states have given large amounts of money to schools through grants that are specifically designated to provide students with hotspots and other avenues for internet access.[134] These new methods used to dispense learning were created in response to COVID-19 and should not be instituted for the limited duration of school closures and high COVID case rates, but should remain intact because of the necessity of online learning and the internet. Thus, increased funding in rural and impoverished school divisions through the refinement of state funding formulas and the continuation of programs that specifically aid high poverty divisions (such as the At-Risk-Add-On in Virginia), will lead to more accessible and equal education for all students.[135]

With the growing trend of telework or remote work caused by the virus’s inception, those rural and low-income public schools need to provide their students with access to internet devices to develop the knowledge and skills as those fortunate enough to live in wealthier school districts. The executive director of a nonprofit organization that aids school in accessing the internet stated, “[g]iven the situation . . . today, it is actually our responsibility to make sure students have internet access at home.” States such as Maryland and Kentucky have hired nonprofits to research and build broadband networks that would be free to k-12 students in rural areas of the state.[136]

If Virginia were to require public education funding like the states in the top 10 for the highest average household median income (including Virginia), the state would need to invest nearly $4.3 billion dollars more a year. Although this seems like an enormous burden and highly costly, the growing digital divide and differences in funding among state schools would shrink and lead to positive results.[137] Studies show that an increase in both the quality of school funding and the amount spent on each student leads to higher test scores and graduation rates.[138] For example, one study found that an additional $1,000 for a minimum of four years would result in positive scores of 91% and for positive educational attainment 92%.[139] States across the Nation, including Virginia, can remedy the ancient inequities rooted in funding public schools that COVID-19 exposed through the development of a more equitable system. Not only will a more equitable funding system address the learning losses caused by online learning and lack of internet access, but rectify the wrongdoings that rural and impoverished communities have suffered because of the impact of the property tax system on education. Therefore, because COVID-19 and the advent of online learning have led to dramatic changes in education, it also exposed the failures of public-school funding and initiated a discussion about what measures the State must take to achieve an equal opportunity for all students.

Camilla E. Watson, How the State and Federal Tax Systems Operate to Deny Educational Opportunities to Minorities and Other Lower Income Students, 72 S.C. L. Rev. 625, 626 (2021).

Id. at 628.

Id.

Id. at 632.

Id.

Cory Turner et al., Why America’s Schools Have a Money Problem, NPR (August 18, 2016, 5:00 AM), https://perma.cc/87ZY-PG3V.

Jonathan M. Purver, Validity of basing public school financing system on local property taxes, 41 A.L.R.3d 1220 (1972).

Id.

310 F. Supp. 572, 574 (W.D. Va. 1969).

Id.

Va. Const. art. VIII, § 1.

Id. § 2.

Watson, supra note 1, at 626.

Id. at 626.

Barbara A. Favola, Virginia Schools in High-Poverty Areas Need Equitable Funding, Wash. Post, Sept. 24, 2021.

Briana Jones and Chad Stewart, High Capacity, Low Effort: Virginia’s School Funding is Low Compared to Most Rich States, The Commonwealth Inst., https://thecommonwealthinstitute.org/the-half-sheet/high-capacity-low-effort-virginias-school-funding-is-low-compared-to-most-rich-states/ (last visited Sept. 8, 2021).

Id.

Id.

Id.

Scott v. Commonwealth, 443 S.E.2d 138 (Va. 1994).

Id. at 139.

Id.

Id.

Id. at 140.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id. at 142.

Id. at 140.

Derrick Bryson Taylor, A Timeline of the Coronavirus Pandemic, N.Y. TIMES, Aug. 6, 2020.

Kelly J. Deere, Governing by Executive Order During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Preliminary Observations Concerning the Proper Balance Between Executive Orders and More Formal Rule Making, 86 Mo. L. Rev. 721, 737 (2021).

Id. at 737.

Id. at 738-39.

Laura Waineman, All Virginia K-12 Public Schools Closed for Two Weeks, wusa9 (March 13, 2020), https://www.wusa9.com/article/news/health/coronavirus/virginia-schools-k-12-close-coronavirus-northam/65-96bea18a-fc57-43f9-889f-0bc878d52aaf.

School Closure Frequently Asked Questions, Va. Dep’t of Educ., https://www.doe.virginia.gov/support/health_medical/office/covid-19-faq.shtml (last visited June 1, 2020).

Id.

Id.

Jim Alrutz, Featured Practice Perspective: Legislative Update: Early State and Federal Responses to Coronavirus-Related, 40 Child. Legal Rts. J. 146, 148 (2020).

Id.

Megan Helton, A Tale of Two Crises: Assessing the Impact of Exclusionary School Policies on Students During a State of Emergency, 50 J.L. & Educ. 1, 7 (2021).

Altruz, supra note 40.

Helton, supra note 42, at 4.

Melissa Murray & Caitlin Millat, Pandemics, Privatization, and the Family, 96 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 106, 109-10 (2021).

Id.

Id.

Id. at 108.

Sophie Tatum, As Learning Moves Online, Coronavirus Highlights a Growing Digital Divide, ABC NEWS (Aug. 25, 2020), https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/learning-moves-online-coronavirus-highlights-growing-digital-divide/story?id=70238572.

Id.

Julia H. Kaufman et al., Which Parents Need the Most Support While K–12 Schools and Child Care Centers Are Physically Closed?, Rand Corp. (2020), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA308-7.html.

Tatum, supra note 49.

Id.

Elliot Haspel, Bail Out Parents, The Atlantic (Aug. 20. 2020), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/08/where-bailout-parents/615415.

Pia Ceres, A ‘Covid Slide’ Could Widen the Digital Divide for Students, Wired, https://www.wired.com/story/schools-digital-divide-remote-learning (last visited July 2020).

Murray & Millat, supra note 45, at 119-20.

Helton, supra note 42, at 10.

Id. at 109.

Osamudia James, Risky Education, 89 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 667, 677 (2021).

Id. at 673.

Ceres, supra note 55.

Id.

Id.

Helton, supra note 42, at 5.

Tatum, supra note 49.

Id.

Helton, supra note 42, at 5.

Id. at 12.

Id. at 11.

S. Chandra et al., Closing the K-12 Digital Divide in the Age of Distance Learning, Common Sense Media & Bos. Consulting Grp., https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/pdfs/common_sense_media_report_final_6_26_7.38am_web_updated.pdf (last visited 2020).

Tatum, supra note 49.

Robin Lake & Alvin Makori, The Digital Divide Among Students During COVID-19. Who Has Access? Who Doesn’t?, CRPE Reinventing Pub. Educ. (June 16, 2020), https://crpe.org/the-digital-divide-among-students-during-covid-19-who-has-access-who-doesnt/

Id.

Helton, supra note 42, at 13.

Id.

Id. at 28.

Lake & Makori, supra note 72.

Id.

Id.

Id.

S. Chandra et al., supra note 70.

Lake & Makori, supra note 72.

Favola, supra note 15.

Id.

Lake & Makori, supra note 72.

Id.

Turner, supra note 6.

Id.

Lake & Makori, supra note 72.

Id.

Emily A. Vogels et al., 53% of Americans Say the Internet Has Been Essential During the COVID-19 Outbreak, Pew Research Center (April 30, 2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/04/30/53-of-americans-say-the-internet-has-been-essential-during-the-covid-19-outbreak/.

S. Chandra et al., supra note 70.

Id.

Andrew Perrin, Digital Gap Between Rural and Nonrural America Persists, Pew Res. Ctr. (May 31, 2019), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/31/digital-gap-between-rural-and-nonrural-america-persists.

Ceres, supra note 55.

Lake & Makori, supra note 72.

Id.

Benjamin Herold, The Scramble to Move America’s Schools, Educationweek (Mar. 27, 2020), https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2020/03/26/the-scramble-to-move-americas-schools-online.html.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Abby Oakland, Minnesota’s Digital Divide: How Minnesota Can Replicate the Rural Electrification Act to Deliver Rural Broadband, 105 Minn. L. Rev. 429, 452 (2020).

Turner, supra note 6 (quoting Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954)).

Oakland, supra note 105, at 453.

S. Chandra et al., supra note 70.

Oakland, supra note 105, at 451-52.

Monica Anderson, About a Quarter of Rural Americans Say Access to High-Speed Internet Is a Major Problem, Pew Res. Ctr. (Sept. 10, 2018), https://perma.cc/949G-AM43.

Id.

S. Chandra et al., supra note 70.

Oakland, supra note 105, at 456.

Helton, supra note 42, at 29.

Id.

Emma Dorn et al., COVID-19 and Education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning, Mckinsey & Co. (July 27, 2021) https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/covid-19-and-education-the-lingering-effects-of-unfinished-learning.

Helton, supra note 42, at 32.

Id.

Emma Dorn et al., supra note 116.

Helton, supra note 42, at 32.

Emma Dorn et al., supra note 116.

Id.

Helton, supra note 42, at 34.

Oakland, supra note 105, at 432-33.

Id. at 435.

Id. at 457.

Renee Morad, 5 Common Stimulus Check Problems—And How To Resolve Them, Forbes (June 20, 2020), https://www.forbes.com/sites/reneemorad/2020/06/20/5-common-stimulus-check-problems-and-how-to-resolve-them/?sh=60de5fd04ccb.

Cary Lou et al., District Funding in Virginia: Computing the Effects of Changes to the Standards of Quality Funding Formula, Urb. Inst. (Dec. 20, 2018), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/school-district-funding-virginia.

Favola, supra note 15.

Id.

Id.

Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

Mark Lieberman, Making Sure Every Child Has Home Internet Access: 8 Steps to Get There, EducationWeek (Sept. 28, 2020), https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/making-sure-every-child-has-home-internet-access-8-steps-to-get-there/2020/09.

Id.

Jones and Stewart, supra note 16.

Lieberman, supra note 133.

Jones and Stewart, supra note 16.

Id.

Id.